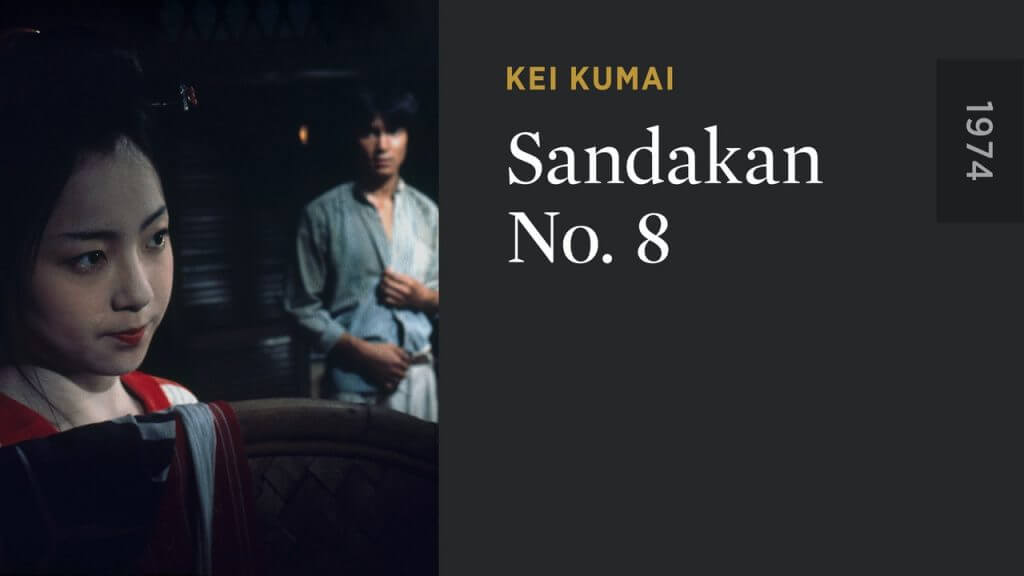

Sandakan No. 8 (1974) is a Japanese film directed by Kei Kumai which focused on the ‘karayuki-san’.

‘Karayuki-san’ is the Japanese term for young women forced into sexual slavery in the 19th and early 20th century. Directly translated, it means ‘Ms. Gone-To-China’, although it was expanded to ‘Ms. Gone-Abroad’ as it saw these young women being trafficked to Southeast Asia, Manchuria and even as far as San Francisco.

The movie was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1975. (It lost to Akira Kurosawa’s Dersu Uzala.)

The plot of Sandakan No.8

The film starts with journalist Keiko Mitani (Komaki Kurihara) who is researching the history of Japanese women who were sex slaves in Asian brothels during the early 20th century.

While researching, she finds Osaki (Kinuyo Tanaka), a former karayuki-san who lives in a shack in a rural village.

Osaki agrees to tell her life as the film goes into a flashback to the 1920s.

Poverty-stricken circumstances led to a young Osaki (Yoko Takashi) being sold by her family to work as a maid.

The location? Thousands of miles away in Sandakan, British North Borneo (present-day Sabah).

Osaki thought she was going to work in a hotel. As it turns out, the establishment was actually a brothel called Sandakan No.8.

She is forced to work as a prostitute at Sandakan No.8 until World War II. During her stay at the brothel, she has a short-lived romance with a poor farmer.

When Osaki finally returns to Japan, her brother and his wife who have bought a house using the money she sent them, turns her away. Osaki’s life can never be normal again due to her past at Sandakan No.8.

In the epilogue, Osaki tells Keiko about a graveyard established for prostitutes who died in Sandakan.

Later, Keiko makes her way to Borneo looking for the cemetery. When she finds the graveyard, Keiko realises that all of them were buried with their feet pointing in the direction of Japan.

It is a gesture to condemn their ancestral home for abandoning them.

Sandakan No. 8 is based on the book “Sandakan Brothel No. 8: An Episode in the History of Lower Class”

When author Yamazaki Tomoko interviewed a former karayuki-san, she gave her the pseudonym – Yamakawa Saki – to protect her identity.

Yamazaki met her by accident during a trip to Amakusa in 1968 while researching on karayuki-san. After a series of interviews with Osaki and her friend Ofumi, Yamazaki wrote the book “Sandakan Brothel No. 8: An Episode in the History of Lower Class” (1972).

Although it was Yamazaki’s first book, it instantly became a national best-seller, with her work considered as a pioneer work on karayuki-san. It was later followed by “The graves of Sandakan 1964” and “The Song of a Woman Bound for America 1981”.

The real-life Osaki was born around 1900. Shortly after her birth, her father died leaving her mother struggling to feed three children.

Osaki’s mother then remarried, this time to her own brother-in-law, moving in with her new husband and his six children. For the most part, however, her mother left Osaki and her siblings to fend for themselves.

In order to survive, Osaki’s brother sold her to a procurer for 300 yen. Osaki had also agreed to go because her best friend was going too. She was only 10 years old.

When Osaki first arrived at Sandakan, she worked as a cleaner in the brothel on Lebuh Tiga in Sandakan.

After she turned 13, she was forced to take on customers.

Osaki’s life at Sandakan No.8

Later, she moved to Sandakan No. 8, also known as Brothel No.8, which was unusually owned by a woman named Kinoshita Okuni. She was also known as Okuni of Sandakan who treated her girls well.

Before coming to Sandakan, Okuni was a live-in mistress to an Englishman back in Yokohama. After he left Japan for good, she moved to Sandakan to open a general store and a brothel.

Osaki became a live-in mistress to an Englishman in Sandakan after seven years working at the brothel.

Interestingly, the arrangement was a facade to hide the fact that the Englishman was having an affair with another Englishman’s wife.

Little is known about the Englishman. Osaki called him “Mister Home” and he worked at Dalby Company which owned a shipyard in Sandakan back then. Mister Home also had a wife and children back in England.

Nonetheless, Osaki was happy with the arrangement. She still received money from Mister Home to send it back to Japan and she no longer took customers at the brothel.

Unfortunately, just like the film, Osaki was rejected by her elder brother and the rest of her family upon her return to Japan.

So where is Sandakan No.8?

Just like Keiko in the movie, Yamazaki made her way to Sandakan in the 1970s.

To her disappointment, there were no traces left from Sandakan No.8 or any other brothels.

However, she did find an old graveyard which is now called Sandakan Japanese Cemetery.

It was founded in 1890 by Osaki’s boss, Okuni. She built it to pray for the souls of Japanese who died in Sandakan.

And just like in the movie Sandakan No.8, they were all buried with their feet pointed in Japan’s direction.