In January 1963, the people of Bau, Siniawan and Batu Kawa experienced a flood like they never seen before.

Apparently, the locals believed that it was caused by the capture of the Daughter of the Sea Dragon King.

Who was the Daughter of the Sea Dragon King and how did she cause the major flooding in these areas? Here is an account of what happened written by Ong Kwan Hin to the Sarawak Gazette on Mar 31, 1963:

Readers of the Sarawak Gazette would have come across a vivid account, and have seen the pictures of the flood at Bau, Siniawan and Batu Kawa by Messrs S Cottrell and Des Carbury in the February issue.

This flood at its peak period in late January, 1963 was the worst ever experienced before in living memory. Various parts of the first division of Sarawak were affected, and in other parts of the country flooding also took place. It was a generally agreed that never before in the known history of Sarawak had there been such calamity.

The Chinese devotees of the various temples offered prayers and supplications all over the country for a heavenly release from the afflictions of the prevailing rain and stormy seas.

Signs were sought for, and horoscopes were cast, and consulted as to what the bad weather and the trouble in Northern Sarawak and beyond augured for the people.

Worshipers and devotees of the various guardian deities who manifested themselves through mediums in trances flocked to supplicate for relief and assurances.

The assurances obtained were disquieting – more affliction in the form of floods or an epidemic of sickness, seemed to be what the gods could presage of the future.

The capture of Daughter of the Sea Dragon King

On the fifteenth day of the second moon (Mar 10), the Lim Hua San Temple situated at Tabuan Road was visited by devotees, who went there to pray with incense sticks and burn joss papers and send up supplications for good weather.

In the midst of the worship one of the worshipers, who was an old woman, went into a trance. While in her trance, in which one of the several deities venerated in the temple manifested itself, the deity proclaimed that yet more terrible flood and form of mad sickness would take its toll.

For months in the Museum at Kuching (so proclaimed the deity) one of the tortoises brought from Muara Tebas had been held captive and she was a daughter of the Sea Dragon King.

The flood waters would one day rise as high as the Museum Building to release this daughter and Princess from the wooden tub in which she was exhibited.

On being asked by the devotees present as to what must be done to alleviate the prevalent bad weather resulting from the wrath of the Sea Dragon King – a deity in his own right – and to forestall such a calamity in store, the deity stated that the Princess must be released.

Pleading for the freedom of the Daughter of the Sea Dragon King

According to the deity, an appeal must be made direct to the Curator of the Museum, and the appeal must be through the writer’s eldest song, Ong Kee Hui, in his capacity as Mayor of Kuching.

On doubts being expressed by the devotees that Mr Tom Harrisson would willingly free the captured tortoise Princess, the deity stated that no matter how difficult the Curator would be, his heart could be made to relent.

If and when Ong Kee Hui had released the Princess the Ong family (according to the deity) would be honoured and visited with blessings for this generation and succeeding generations.

The Sarawak Tribune in its issue dated 14th March on the trance stated that it was medium at the Muara Tebas temple. This is not correct.

From my knowledge of both temples I know, and this can be confirmed, both do not have mediums.

I went to see the senior monk living at the Lim Hua San Temple to get a first hand account a few days before sitting down to record the above facts.

He could not tell me which deity, of which there were several in the temple, had manifested itself through the old woman worshiper.

It was generally believed to be one of the Buddhas. The identity of the old woman was not discovered as this might lead to understanding, and personal embarrassment in such a case for her and her family.

A deputation of three ladies- one the wife of a proprietor of a well-known firm in Kuching, another whose husband works with a prominent textile firm, and one of the wife of a physician -called on Mrs Ong Kee Hui on the 12th March.

Mrs Ong was told the facts and as Kee Hui was not in, she promised to take up the matter to him.

Meeting up with the Sarawak Museum

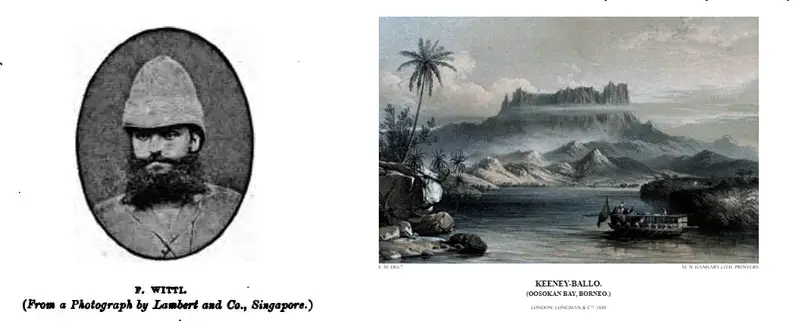

I was consulted, and on the morning Mar 12, 1963, Kee Hui made a request to Tom Harrisson, the Curator of the Sarawak Museum for the release of the tortoise to the Muara Tebas temple as it belonged to that area.

Harrisson agreed to hand it back through me as one of the trustees of the temple.

On the afternoon of the 13th March at 2.30pm, I went down to the museum accompanied by my wife, Kee Hui and his wife, and my ninth son Ong Kee Pheng to effect the release of the Princess. The Information Office which acted as ‘go-between’ was there to photograph and record the occasion. Mr Lo Chi Yin (Museum Archivist) was there to meet us.

In recognition and appreciation of Mr Harrisson’s courtesy in freeing the Princess, the Hokkien Association which looks after the Muara Tebas Temple, and of which Ong Kee Hui is the Chairman, presented the Sarawak Museum with three Jade Buddha statues.

The ‘go-between’ -the Information Office was promised the gift parchment scroll, to be suitably inscribed with an invocation to the Three Kong Deity asking for countless blessings to be bestowed on its work in the future. The Princess was left in the Museum for that night.

A search for a launch was without result, but the Heng Hua fishing folk offered us the use of a Kotak.

These people had been following the fate of the Princess with deep interest. They had even thought and talked of liberating her by kidnapping, and then be the hostages to be put in jail for this unlawful act.

As their livelihood is in the sea, they are as a people extremely careful to keep on the right side of the Sea Dragon King.

Thus they would have preferred to face an irate mortal Curator than the wrath of a deity.

Releasing the Daughter of the Sea Dragon King

Eventually my son Henry Ong succeeded in renting a speedboat from the Kuching Boat Club for $35. This plus fuel and driver charges amounted to $54 for the whole trip the cost of which were subscribed to by some devotees and members of my family.

On the morning of the 19th day of the 2nd moon (Thursday 14th March, 1963) we called at the museum for the Princess at 8.30am.

We then drove up to Pending and embarked on board the speedboat. This day was the Birthday of Kuan Im – the Goddess of Mercy, a very auspicious one for liberating the Sea Dragon Princess.

The party consisted of my wife, my fifth son Henry, Mrs Ong Kee Hui, three of the women devotees (including the two who came originally to see Mrs Ong Kee Hui) and on old monk from the Lim Hua San Temple, who chanted prayers and invocation all the way.

We were met at Pending by the Tua Kampong Dawi Aron of Kampong Semilang, Muara Tebas, who told us that he had heard the story about the Princess over the radio the previous night. He expressed regret that his capture of Her Highness had caused so much trouble.

He had found the Princess in the trap he set for catching prawns.

When we later arrived back in the afternoon we found him still waiting at Pending to find if the Princess had been safely released.

Prayers at Muara Tebas Temple

On arrival at Muara Tebas at 9.30am we brought the Princess up to the Temple.

The chief nun who greeted us found that Her Highness was the same tortoise which had previously been brought by her from a Malay fisherman and liberated in the sea.

There was a small hole punched in the shell where she had put stick of incense when after chanting prayers, she had released her.

We offered incense sticks, joss papers and our prayers to the deities at the Temple. I suggested that after having been reared in fresh water, the Princess should be released on dry land.

But the deity Kuan Im indicted by signs that she must be given back to the sea.

That afternoon, on our way home, we took the speedboat right out to the middle of the exactly facing the temple.

There, while the old monk recited prayers and invocations, Her Royal Highness, daughter of the dreaded and mighty Sea Dragon King deity was released.

As she went back to her own element she went into and out over the water three times, each time stretching out her royal neck to look hard and long at us.

Then she sank away from sight and while we all repeated the “Lam Boo Oh Mee Toh Hood”, she disappeared to join the denizens of the deep.

The Consort of the released Sea Dragon King’s daughter

About one week after the Princess of Sea Dragon King was released at Muara Tebas, another tortoise was found at Matang.

This time the temple devotees claimed that it was the Consort of the Released Princess.

It was reported the tortoise was sold to a bus driver who then handed it over to the Hun Nam Siang Tng Temple of Sekama Road.

After consulting the deity, the devotees released it on the birthday of the deity at the Guan Thian Siang Tee Temple in Carpenter Street which fell on the third day of the third moon.

That year, the date fell on March 27, 1963.

This was not the first time a mystical creature was held responsible for a flood in Sarawak. In 1942 for example, a dragon was believed to be the cause of a major flood in Belaga.