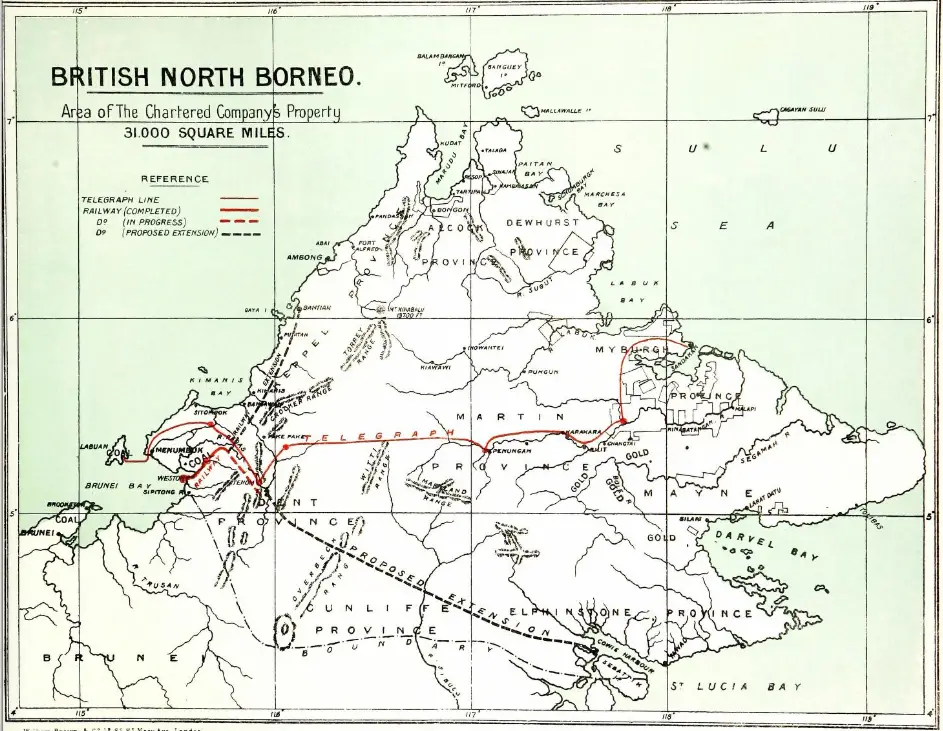

Located in Sandakan Bay, Malaysian state of Sabah, the Berhala island is a small forested island.

Before World War II (WWII), the island was used as a layover station for labourers coming from China and the Philippines. There was also a leper colony on the island.

Then during WWII, the Japanese used the quarantine station as a makeshift internment camp for both prisoners-of-war (POWs) and civilian internees.

The POWs and civilian internees were stationed on Berhala Island before they were sent Sandakan POW Camp or Batu Lintang Camp respectively.

In June 1943, the island witnessed a thrilling escape of eight POWs worthy enough to inspire a Hollywood movie.

The eight-member group later became known as The Berhala Eight.

Jock McLaren of Berhala Eight

The Berhala Eight were Lieutenant Charles Wagner, Sergeant Rex Butler, Captain Raymond Steele, Lieutenant Rex Blow, Lieutenant Leslie Gillon, Sapper Jim Kennedy, Private Robert “Jock” McLaren and Sergeant Walter.

Among them, the widely known one was Jock McLaren.

During World War I (WWI), McLaren was serving in the British Army. After the war, he moved to Queensland, Australia where he was working as veterinary officer.

When the WWII broke out, he joined in the Australian Imperial Force.

According to Senior News, McLaren was assigned in British Malaya when Singapore fell to the Japanese army.

He was then captured as a prisoner of war alongside 80,000 British, Indian and Australian troops in Singapore.

However, McLaren was not going to bow down to the Japanese and stay in Changi prison quietly. Together with two other soldiers, he made his escape from Singapore.

They almost made it to Kuala Lumpur before they were betrayed to the Japanese by the local Malays.

By September 1942, McLaren was back where he was first imprisoned at Changi prison. But, ass the saying goes, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try, try again.”

So he planned his escape again. This time, he managed to slip into a group of prisoners called ‘E’ Force.

As part of ‘E’ Force, McLaren was among 500 British and 500 Australian POWs who departed Singapore on Mar 23, 1943.

They boarded SS De Klerk, an abandoned Dutch passenger-cargo liner which was refloated by the Japanese who renamed it ‘Imabri Maru’.

The ship reached Kuching, Sarawak on Apr 1 and departed eight days later for Berhala Island.

On Apr 14, the men of ‘E’ Force arrived on the island where they stayed for six weeks before being transferred to the Sandakan POW Camp.

Life on Berhala Island for the ‘E’ Force

According to the War Memorial Australia, the Berhala Camp was enclosed by barbed wire, was set back about 160 yards from the sea.

The toilets were outside the wire, which gave intending escapees and excuse for being outside the camp.

Once again, McLaren tried to escape. He knew that once he been transferred to Sandakan POW camp, it would be harder for him to escape. For him, the escape had to be made from Berhala Camp.

Together with Kennedy, the duo joined a wood-carrying party during their stay at the Berhala Camp. This allowed them to move around the island while planning an escape plan in their heads.

They saw the leper colony there had a small boat. McLaren then planned to use it for their escape.

Meanwhile, another escape party was being formed by Steele, Blow, Wagner, Gillon and Wallace.

Both parties made contact with a corporal from North Borneo Constabulary, Koram bin Anduat to help with their escape.

Koram advised them to make for Tawi-tawi island in the Philippines which was about 250km west of Sandakan.

McLaren then realised that it would be a long, hard and dangerous row to Tawi-tawi. He needed another man so he approached Rex Butler.

As described by Hal Richardson in his book One-man War: The Jock McLaren Story (1957) on the escape as:

“A tall thin grazier from South Australia who had been a buffalo shooter in the Northern Territory and could shoot a buffalo’s eye out at fifty yards. Butler appeared to have the necessary nerve too. There was no room in the party for a man who was likely to crack when the heat was on.”

McLaren believed that Kennedy could withstand the pressure. After watching Butler moving around the camp and his coolness under the provocation of guards, he was confident that Butler was the man for his escape team.

McLaren, Kennedy and Butler made their escape from Berhala Island

On June 4, 1943, the Japanese bought a large barge and ordered the POWs to be prepared for transfer to Sandakan the next morning.

The Berhala Eight took it as a sign that they must escape that night before being transferred.

Under the pretense of using the restroom, the eight Australians left the camp in the middle of the night.

The men then collected their hidden supplies and clothes before going into hiding in the forest.

The next day, after stealing a boat from the leper colony, McLaren, Kennedy and Butler began their gruelling journey to Tawi-tawi.

With no sail, and with just the use of wooden paddles, the three men paddled their way through the raging ocean for their lives.

The men travelled by night in order to avoid the tropical heat.

Even with their frail bodies after spending the past 16 months on little food in the POW camps, the trio made it to Tawi-tawi island.

Thankfully, the men were welcomed by friendly locals on the island.

Koram helping Steele and the rest to escape Berhala Island

In the meantime, Steele and the rest four men were still on the Berhala Island.

When McLaren and his group stole the boat from the lepers, it did not go as smoothly as planned. The lepers actually keep on pursuing them.

After that, the lepers went to the Japanese to report on the incident.

Now, it became dangerous as the Japanese are looking for the remaining five escapees.

That was when Koram and his wisdom came to work.

According to Bayanihan News, on the night of the last POWs had been transferred to Sandakan, Koram borrowed a pair of boots from one of his Australian friends.

“Then he quietly made his way to the cluster of houses near the shore. He untied one of the boats belonging to an islander, made a hole in the bottom of the boat and shoved it into the flowing waters of the estuary where it was carried some distance away before it sank out of sight in the deep water.

He stole two more boats, and did the same with them. He then put on a pair of Australian army boots which he had managed to get hold of earlier, and stomped around on the spot on the seashore, leaving a lot of tracks. Then he quietly returned to the mainland undetected.Early the next day, there was a great hue and cry when the three islanders awoke to find their boats gone. They reported the matter to the Japanese, who went to investigate.

When they saw the boot prints in the mud they concluded that the Australian POWs must have taken the boats and escaped from the island, and they immediately mounted a search at sea. They never realized that the escapees were still on the island.”

Steele and the rest made their escape using kumpit

With the help of local guerrillas, the remaining five POWs made their escape from the island.

Using a local boat called kumpit, the POWs were told to lie in the hold. Then planks were placed on them with sacks of rice on top of the planks.

There was one nerve-wracking moment when a Japanese destroyer stopped the kumpit to check on it.

Thankfully, the Japanese decided not to board the boat but let it pass.

On June 24, all members of The Berhala Eight reunited on Tawi-tawi.

The Berhala Eight staying to fight

Due to lack of transportation and the need for experienced leaders, The Berhala Eight stayed with the guerrillas to fight against the Japanese.

Unfortunately, Butler was killed in action while on a fighting patrol at Dungun river of Tawi-tawi.

His body was then decapitated by the local Moros who were friendly with the Japanese.

Meanwhile, the rest of the POWs made their way to Mindanao to join the American and Filipino guerillas under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Wendell Fertig.

On Dec 21, 1943, Wagner was killed during an engagement with the Japanese at Liangan in Lanao province.

After battling with the Japanese for some time, Gillon, Steele, Wallace and Kennedy were evacuated from the Philippines by the USS Narwhal on Mar 2, 1944.

Meanwhile Blow and McLared remained with the guerrillas until the Australian government requested their return.

The impact of Berhala Eight

In the book Fighting Monsters: An Intimate History of the Sandakan Tragedy, Richard Wallace Braithwaite described the impact of the escape on the remaining POWs.

“The key to the success of the ‘Berhala Eight’ was help from local people, and this worried the Japanese. From now on, they killed recaptured escapees and punished the camp from which they escaped through cutting rations. As a result, senior Allied officers were by this stage strongly discouraging escapes.

“The Australian prisoners probably did not realise how seriously the Japanese viewed this development of local collaborators helping prisoners escape. All this undoubtedly reflected poorly on Hoshijima (Sandakan POW Camp’s Person-in-Charge Captain Susumi Hoshijima) and invoked a strong response. While all POWs at Sandakan suffered harsher treatment, the Australians were seen by the Japanese as the main problem.

“Most prisoners now acknowledged the likely consequences for the individual and for the camp of any escape attempt. Most became content to stand on the side of the chessboard but continued to dream of escape.”

When the Berhala Eight made their escape, they would not have thought of how the Japanese would retaliate against the remaining POWs and local people who tried to help the prisoners.

Nonetheless, their escape from Berhala Island saved their lives as they then missed the infamous Sandakan Death Marches and executions of Sandakan POW Camp.