With less than 300 Sihan people in Sarawak (as of 2012), any stories about their legends, customs and histories are very precious and important.

As recorded by Benedict Sandin in “Notes on the Sian (Sihan) of Belaga” for the Sarawak Museum journal, the Sihan speak the same language with Punan Bushang and Punan Aput, and not with other Punans.

In ‘Language Vitality of the Sihan Community in Sarawak, Malaysia’ by Noriah Mohamed and Nor Hashimah Hashim, the Sihan people, who identify themselves as Punan, migrated to Belaga from Namang River, after moving from their original settlement in Mujong near the Baleh River.

1.The ancestors of the Sihan people

A Sihan man named Jingom Juroh once told a story to Sarawak Museum about the ancestors of the Sihan people.

“I know that a spirit begot our first ancestor called Kato’o. He was born overseas. Kato’o was a brave hero who fought and won many wars against other people. Upon seeing his bravery his children began to become afraid of his actions. Knowing that his children worried about him, he ordered them to use only bamboo spears, and not with other kinds of weapons so that they could not harm him.

However, they killed him with the bamboo spears. After his death the bamboo spears which pierced him grew to become a high mountain. We do not know where this hill is, but according to our history it is somewhere overseas.

Kato’o sons immigrated from overseas. Their names were Belawan Jeray and Belawan Tiau. The two brothers lived in the Mujong. From Mujong Belawan Tiau led his followers to migrate eastward to Kapuas. Therefore in the Kapuas quite a number of Sian (Sihan) lived.

Belawan Jeray died in the Mujong. After his death his son named Maggay migrated to the Pilla and died there. After his death his son Gawit moved to Seggam and died there.”

Mujong is a tributory of Baleh river and Pilla is a tributory of the Rajang river.

2.Life of the Sihan people before they settled in the longhouse.

Unlike most indigenous groups in Sarawak, the Sihan people originally lived in huts like the Penan people.

They did not live in longhouses.

Jingom was 56 years old when he shared this to the Sarawak Museum in 1961: “We Sihan have never joined other races to live in longhouses. I remember that we start to farm when I had already grown up to about the age of thirteen years. We started to live in longhouses from the time we were taught to farm by the Kejaman chief Akek Laing alias Matu.”

He added, “During our nomadic days we have no other tool to use other than the axes. We got iron by bartering with the Kejaman our jungle produce such as rattan baskets and mats. Till this day though our people still can make baskets and mats, but we do not keep them because we sell them to the Kayan and others.”

The Sihan people also did not make blow pipes. Only after they traded blowpipes from the Penan did they hunt for birds and animals. Before that, they relied on fish as their source of protein.

Additionally, the Sihan people did not rear domestic pigs but chickens. With regards to fruits, they collected wild fruits when they were nomadic. They started to plant fruit trees after they settled in longhouses.

3.The legend of Batu Balitang

When the Sihan people were still living at Mujong, there was a man who went out shooting animals with his blowpipe.

As he roamed the forests, he did not find anything.

When he was on his way home, he saw a huge shining animal standing on the bough of a tree. It looked like a rainbow.

The man shot at it several times with his poisonous darts, but could not kill it.

The hunter returned to his hut to bring his friends for help.

While explaining to his friends what happened, they heard a very loud sound as if something falling from the sky.

Everyone, men and women alike, ran toward the source of the noise and found an animal lying on the ground.

Rejoicing over the fresh meat, they cut the animal up and cooked it. Everyone in the village ate the meat, except a pair of brother and sister.

Unbeknownst to the villagers, the animal they feasted on was a demon. That night when they slept, the demon’s wife came.

As she came, she danced from one home to another, looking for the people who ate her husband.

She found that all except two, had eaten her husband. Hence, she ordered the brother and sister to escape instantly and never look back.

The demon’s wife ordered them to go to a certain stream not far away on the left of the Mujong above their village. In order that they may know this place, on her way to the village the demon’s wife had cut a certain small tree as a sign.

The two siblings fled as directed. After they had gone, a great wind blew and a heavy rain began to fall. During the storm, the houses gradually became stone, becoming what has become recognised today as Batu Balitang.

After all the villagers became stones and boulders, the siblings got married and became the ancestors of Sihan people.

4.The truth about headhunting among the Sihan people

While most indigenous peoples in Borneo have a long history of headhunting, the Sihan people tried their best to avoid them.

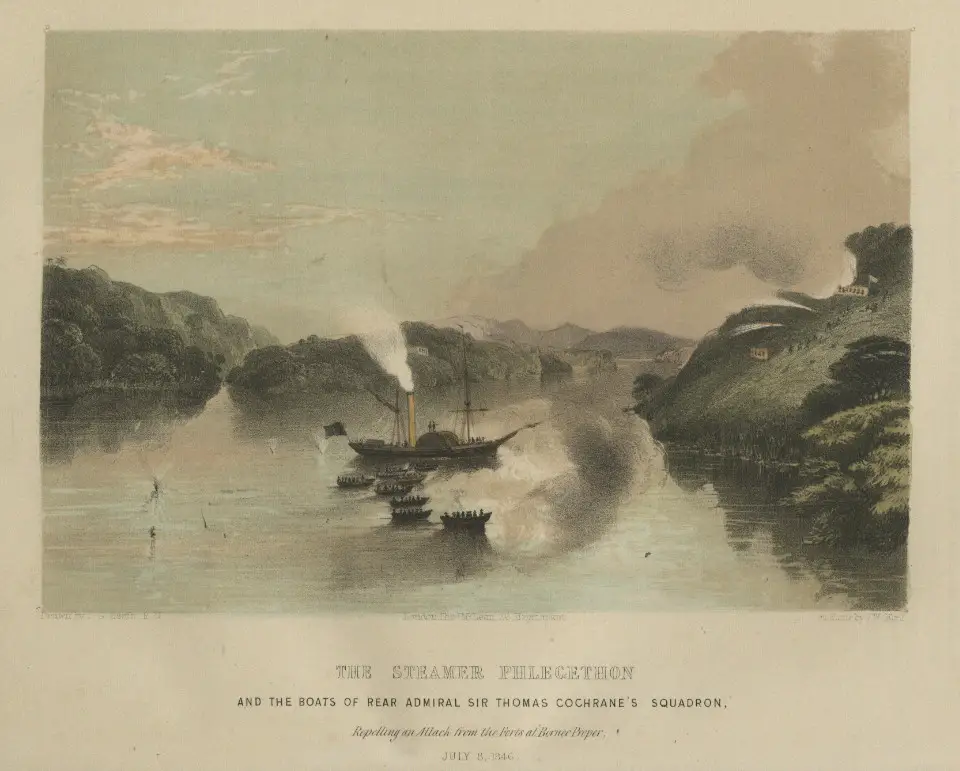

However, they did fight against Iban and Bukitan headhunters about a century ago.

Many people were killed on both sides of the war.

The Sihan people reportedly did not value the heads of the enemies as trophies, even throwing them away.

5.The burial customs of the Sihan people

Immediately after a Sihan person dies, their bodies are cleaned with water. After that, the deceased is dressed in clothes made of tree bark.

All of their possessions like axes and baskets must be buried with them.

Unlike the Kayan who used to erect Salong, or burial poles, to bury their dead, the Sihan people will cut a tree for the coffin.

When it is complete, the coffin is placed inside for burial. The burial usually takes place on the second day after death.

Then two nights after the burial, a fire will be lit outside the house. The Sihan people believed that in the nights after the burial, the soul of the deceased will wander about intending to return to the house. As for offerings, they place sago by the fire.

The Sihan traditional belief is that when one passes away, thunder is usually sounded. With the sound of this thunder, it is believed that the soul of the deceased is carried away to heaven above.