An Iban chief is always associated with courage and bravery but what happened when a photo taken of them?

Margaret de Windt or better known as Ranee Margaret married the second Rajah of Sarawak, Charles Brooke in 1869.

At the young age of 19, she became the first Queen of the Kingdom of Sarawak back then.

During her husband’s reign, the Ranee showed many interests in her multiracial subjects’ cultures and traditions.

From Malay gold-embroidered fabrics called keringkam to painting the beautiful landscape of Sarawak, Margaret also enjoyed taking photographs.

She even published some of her photos that she took in her 1913 autobiography My Life in Sarawak.

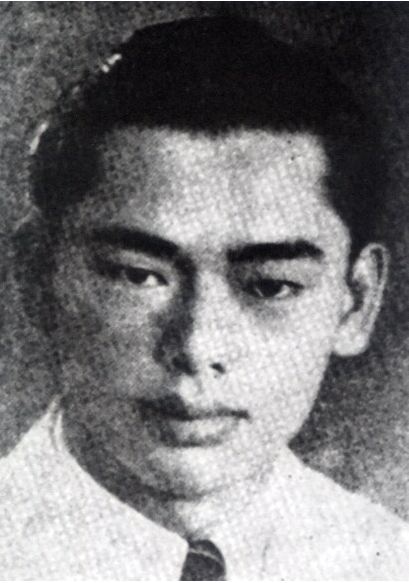

There was one photo that stood out; a photo of Sea Dayak Chief in full warrior attire.

“Let those who look upon my picture tremble with fear!” – Panau, Iban chief

Panau is the man who stood before the Ranees’ camera in this photograph. Margaret wrote that he was an Iban chief who often visited the Rajah and Ranee at their bungalow in Simanggang (now known as Sri Aman).

As a warrior, Panau and his tribe accompanied the Rajah Muda, Vyner on many expeditions up the Batang Lupar river.

The Ranee described him as humble, kind, loyal and talkative. This Iban chief was also described as a funny fellow (although Margaret admitted she didn’t get his sense of humour).

The Iban chief had showed interest in her camera, amazed by the miracle that a photo could came out of a box.

So one day, Margaret decided to take Panau’s picture. And what happened next might not what we expected from a headhunter.

While he was posing for the camera, Panau said: “Let those who look upon my picture tremble with fear!”

Panau’s reaction to his own photo

After the picture-taking session, the Ranee was kind enough to take Panau into the dark room to watch her develop the picture.

Margaret wrote, “He looked over my shoulder as I moved the acid over the plate, when he saw his likeness appear, he gave a yell, screamed out “Antu (Ghost!)” tore open the door, and rushed out, slamming the door behind him.

Mind you, this photoshoot took place around 1896 when photography was rare. Plus, when Panau was glancing over to look at the photo, his picture was still somewhat foggy.

Thankfully, the Iban chief eventually got over his fear and even accepted one of the prints.

Maybe somewhere out there, in one of the longhouses in Sri Aman, Panau’s descendants have that copy of this Iban warrior holding a shield in one hand and a spear in the other.

Besides Margaret’s My Life in Sarawak, Panau’s photo can also be found on display at ‘The Ranee: Margaret of Sarawak’ exhibition at the Old Courthouse.

Read My Life in Sarawak by Ranee Margaret Brooke here at Project Gutenberg.