Kayu raja or raja kayu in Malay, which translates to the ‘king of wood’, is a type of wood widely found in Malaysia. Scientifically, it is known as Agathis borneensis.

It is also commonly known as borneo kuari or damar minyak among the Malay community.

Despite it being classified as ‘endangered’ in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, it is still in demand among the locals in Sarawak.

It is considered one of the most valuable and sought-after timber trees in Southeast Asia. Commercial-wise, Agathis borneensis is wanted for its high quality resin. Plus, its wood can be used to make music instruments, boats as well as furniture.

But coming down to Sarawak, a place where kayu raja can be found apart from Sumatra, Peninsular Malaysia and the rest of Borneo, this wood is utilised for more daily use.

For a cure and more

According to wood crafter Christopher John, the king of wood is believed to have medicinal purposes.

He stated, “You can use it for medicine. Scrape a bit of the wood and boil it in hot water for few hours before drinking it like a tea. The locals believe it can cure for diabetes, high blood pressure and even diarrhea.”

On top of that, it is also a traditional cure for headaches, fevers and muscle pains.

Christopher who is a Bidayuh, added that the kayu raja can also be used externally. “Let say you have scratches or cuts and even insect bites, you can apply the boiled water of kayu raja on your wounds.”

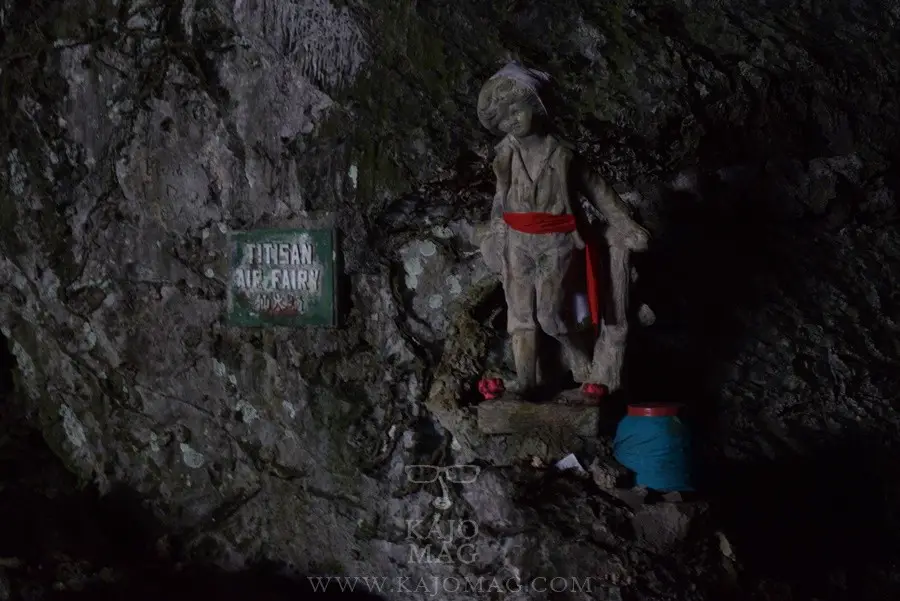

Besides its traditional medical practices, some local Sarawakians believe that the wood works as a protective charm during hunting or jungle trekking.

“If you carry a kayu raja on you when you are going into the jungle, no wild animals would dare to attack you. Some people also believe it will protect you from witchcraft.”

Kayu Raja in other cultures

Feng shui practitioners also believe in the power of kayu raja. It is known for its ability to dispel bad energies from life. Keep a kayu raja on you and your bad luck will slowly subside.

Furthermore, some also believe keeping a piece of this wood as an amulet will increase wealth and career opportunities as well as enhance your charms.

A quick Google-search for kayu raja will reveal a list of websites selling it as a charm.

But how would you know if it’s the real deal? Christopher says to just shine a light through it and you will know.

“The light from the light source will glow red if you shine it through a real kayu raja.”