It is the 1920s. Imagine you are a pastor’s wife, and have sailed thousands of miles from your home to live in a very foreign country.

You don’t speak the local languages so there is no way you can understand their cultures or customs.

Your husband is always away from home preaching to people you refer to as the ‘wild men’ with hope the news of the Gospel will ‘civilise’ them.

And you stay at home with your servant girl who often clashes with you because she is not running the chores according to your American way.

The only way you could learn about this foreign place you are living in is through your husband and other Westerners around you.

By the time you return to your home country, you write a book and publish it under the title ‘With the Wild Men of Borneo’ (1922), which is what Elizabeth Mershon did.

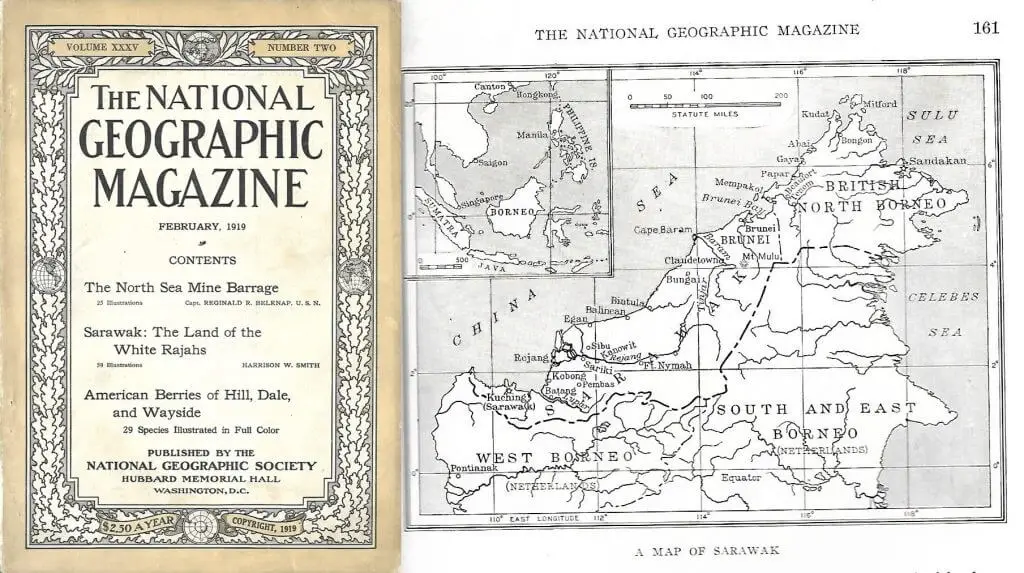

Elizabeth and her husband Leroy Mershon were stationed in Sandakan in the 1920s as part of the Seventh-day Adventist North Borneo Mission.

Her book ‘With the Wild Men of Borneo’, obviously was by no means an anthropology book but was based on her experience here in Borneo.

For the most part, it offers a glimpse of life in Borneo before World War 2, and also the Western perspective of the ‘civilising mission’ which can be seen in Mershon’s descriptions of Borneans as part of an introduction in the third chapter of her book.

These descriptions are based on her personal opinions which Mershon seemed to have gathered from hearsay around her.

So here are some of Elizabeth Mershon’s eyebrow-raising descriptions about the so-called ‘Wild Men of Borneo’:

1.There are ‘two classes’ of Dayaks and one of them is ‘more truthful than the other’

“There are two classes of Dyaks. Those living inland are called Land Dyaks; those living on the coast are called Sea Dyaks.”

“The Sea Dyak, unlike the Land Dyak, is truthful and fairly honest.”

2.The Ibans are descended from the Bugis?

“The Sea Dyaks are not as pure a race as the Land Dyaks, having intermarried with the Bugis from Makassar, in the Celebes.”

3.The description about Bajau people

“On the east coast of British North Borneo are found the Bajaus, or Sea Gypsies. They are a lazy, irresponsible race, building their houses over water, but living almost entirely in their boats. They are of Malay origin, although much darker and larger than the Malays. Taking each day as it comes, and never troubling about what is going to happen tomorrow, they pick up a scanty living along the seashore, catching fish, and finding turtles’ eggs, clams and sea slugs. They lead a wild roving life in the open air, plundering and robbing at every opportunity.”

4.The Bajau are not the only ‘lazy people’ in Borneo according to Mershon

“The Sulus are very lazy, independent and troublesome. Yet they are very brave, and make the best sailors and traders among the islands.”

5.Perhaps ‘the laziest people’ in Borneo according to Mershon are the Muruts

“A very low race called the Muruts live in the interior, on a mountain range near the west coast. These people simply will not work. They eat food they can put their hands on. No matter how dirty an article of food may be, and no matter how long an animal may be dead, it is all the same to the Muruts; they eat it and seem to enjoy it.”

6.The Bruneians don’t seem to be hardworking either

“The natives living in Brunei are called after the name of their country. They too are very lazy; but when they have a mind to work, they make good fishermen.”

7.Finally, the last group of ‘lazy people’ of British North Borneo

“There are also a few Malays and Javanese in British North Borneo. The former are naturally lazy and do not care to work. The Javanese make fairly good gardeners for the Europeans.”

As patronising as Mershon might sound, she did grow fond of Borneo.

In the very first paragraph of her book, “From my childhood days until I arrived in Borneo, all I knew about the country was that it was where the wild men lived, and I always imagined that they spent most of their time running around the island cutting off people’s heads… Before you finish what I am going to tell you about distant Borneo and its people, I hope you will have learned that the ‘wild man from Borneo’ is not such a bad fellow after all.”