Borneo in the 21st century is heaven for all adventurers out there. Here you can find a piece of everything, be it a sandy beach or chilly mountain, exotic animals or unique culture; we have it all.

Plus, the people of Borneo are known for their friendliness and generally being good hosts. It is a vast contrast from what it was like two centuries ago.

To be sure, 19th century Borneo would not have made it to any vacationer’s list of ‘places you must visit before you die’, because, well, there was a high chance that you could actually die.

Rampant headhunting, wild animals, tropical diseases, hostile locals and piracy were just some of the cause of deaths for many explorers.

Regardless, these factors did not stop many Europeans from coming to Borneo to explore the island.

Some survived their trips while others met their ends here in Borneo.

Here are five European explorers and their horrific deaths in 19th century Borneo:

1.Robert Burns

Who was he?

He was a Scottish trader and explorer who became the first European to visit Kayan territory in Borneo.

Burns left Glasgow for Singapore in the 1840s and worked on the island with a Scots-owned trading company, Hamilton Gray.

He then first sailed to Labuan where he sought permission to travel to Bintulu.

Burns reportedly set foot in Bintulu around 1847 before making his way to Rajang and Baram rivers to mingle with the Kayan people.

During this time, he learned about Kayan culture, jotting down their vocabulary all the while.

His paper about the Kayan was published in the Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia in February, 1849.

How did he die?

Burns died a horrific death – decapitated by pirates while sailing off the northeast coast of Borneo island.

Aboard the British registered schooner Dolphin, Burns planned to visit the Kinabatangan river to trade.

Somewhere at Maludu bay, a group of pirates managed to disguise themselves as traders and went onboard the Dolphin.

The pirates attacked Burns and his crew when they lowered down their guards as they thought their ‘guests’ were just wanting to trade.

According to the surviving crew, Burns’ head was severed from his shoulder in one blow.

Read more about Robert Burns here.

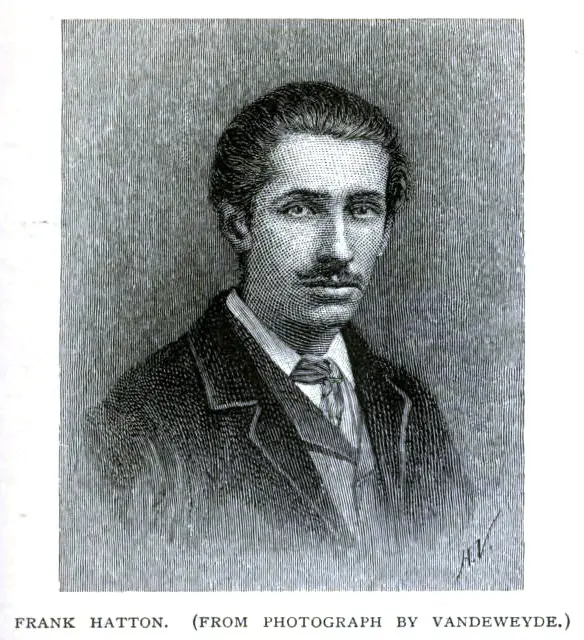

2.Frank Hatton

Who was he?

Born in 1861, Frank Hatton was an English geologist and explorer.

He joined the British North Borneo Company as a mineral explorer.

His job in British North Borneo (now Sabah) was to investigate the mineral resources in the country.

During his journey, Hatton became the first White man that ever made contact with some of the local tribes such as the Dusun.

How did he die?

Hatton died in 1883 due to accidental shooting from his own gun.

It is believed that his Winchester rifle got tangled in jungle creepers, went off and shot him in the chest.

His last words were in Malay saying to his servant Odeen, “Odeen, Odeen mati saya!” (Odeen, Odeen I am dead!) while resting his head on his servant’s shoulder.

Hatton’s last expedition was to find himself an elephant and acquire its tusks.

If he was to succeed in doing so, Hatton might have been the first European hunter to do so in North Borneo back then.

Read more about Frank Hatton here.

3.Franz Witti

Who was he?

He was a former navy officer in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and one of the first few Europeans to explore the northern part of Borneo.

Witti was hired by the British North Borneo Company in 1877 to make a survey of the natural resources in the area.

But before that he already conducted several surveys on his own.

Witti was also known to be the first person who discovered oil about 26km outside of present-day Kudat town in Sabah.

How did he die?

Witti got caught between a tribal feud of two different Murut groups.

During his last expedition which started in March 1882, Witti arrived in Limbawan somewhere near Keningau.

The local Murut chief named Jeludin warned him and his party not to travel to Peluan because there was a feud between Jeludin’s group of Nabai and Peluan.

However, Witti continued his journey and arrived in a village.

There, his group was ambushed by some hundreds of headhunters reportedly from the Murut Peluan group.

The Murut Peluan group attacked Witti and his party because they were friendly with their enemy, from the Murut Nabai group.

Some reports said that he was killed by a spear while others claimed it was a blowpipe that took his life.

Witti didn’t die without a fight as he killed two men using his revolver.

Read more about Franz Witti here.

4.James Motley

Who was he?

Had James Motley lived longer, it is arguable that he might have been comparable to his near contemporary in Borneo, Alfred Russell Wallace.

Born in 1822, Motley first came to Labuan in 1849 to pioneer coal mining for the Eastern Archipelago Company.

There, he did not have a good relationship with fellow naturalist Hugh Low at that time.

He then left Labuan and spent some time exploring the coast of Sumatra until he found his way in Banjarmasin in the south eastern part of Borneo.

Motley is credited with making the first list of Borneo birds and had collected over 2000 plants in Borneo.

How did he die?

Motley, his wife, two daughters and son were among the 100 Europeans killed during the Banjarmasin War.

The war was a power struggle between Sultan Hidayatullah II of Banjar and the illegitimate grandson of the former sultan Tamjied Illah.

During the war, all the Europeans – including the missionaries – were killed by rebels.

Prior to the massacre, on April 18, 1859, Motley had actually written a letter to his father on the Isle of Man assuring him that there was no need to worry.

A mere 12 days later, Motley and his family were found dead.

Read more about James Motley here.

5.Georg Müller

Who was he?

Born in 1790, Georg Müller was a German-Dutch engineering officer who served in the French army during the Napoleonic Wars.

After the Battle of Waterloo, Müller became a civil servant under the Dutch Indies.

As part of his job, he represented the Dutch government to make official contact with the sultans of Borneo’s east coast.

How did he die?

The circumstances surrounding his death remain unconfirmed to this day.

In 1825, he visited the Sultan of Kutai requesting permission to explore the interior part of Borneo.

The sultan was reluctant to give his permission since the area was beyond his territories.

Nonetheless, Müller went up the Mahakam river with a dozen Javanese soldiers.

From here, the details of what happened get blurry.

It is understood that he managed to cross the watershed into the Kapuas basin.

He was killed possibly around mid-November, 1825 somewhere on the Bungan river, at the Bakang rapid.

The general understanding is that Müller and his party were killed by the local Dayak group.

As for which specific group, Dutch explorer Anton Willem Nieuwenheis believed that the Pnihing was responsible for Müller’s death. The Pnihing or Punan Aoheng of East Kalimantan belongs to the Punan Bah ethnic group.

The Müller Mountains, a mountain range in Central Borneo which extends along the northern border of Kalimantan were named after him.

The mountains are the source of the Kapuas watershed where Müller became the first European to visit the area.