Here are 50 very random historical facts about Kuching you need to know

1.Kuching is not the first capital of Sarawak.

The first capital of Sarawak was Santubong which was founded by Sultan Pengiran Tengah in 1599 and then Lidah Tanah founded by Datu Patinggi Ali in the early 1820s.

2.There were geographical and political reasons on why Kuching was chosen as the capital.

Kuching was founded in 1827 by the representative of the Sultan of Brunei, Pengiran Indera Mahkota.

Craig A. Lockard in his paper The Early Development of Kuching 1820-1857 explained why Mahkota chose Kuching.

“Selection of Kuching as the site for a new administrative centre allowed Mahkota to avoid the jealousy and resentment his appearance would arouse among the local elite at Lidah Tanah while at the same time insuring him settlement in which he would have full control. The decision also made geographical sense, as few good existed between Lidah Tanah and the sea, most of them either too exposed to the sea-going raiders then infesting the coast, or suffering from poor soils and lack of fresh water. Located just south of the coastal swamp, Kuching was convenient to both the river mouth 21 miles away, and the antimony mines 25 miles upriver. Finally, distance from the sea, availability of hills on which to build forts, and narrowness of the river all made Kuching easily defensible.”

3.The largest archaeological site in Malaysia is in Santubong

According to the Sarawak Museum website, Santubong is in fact the largest archaeological site in Malaysia, compared to Lembah Bujang in the Peninsular Malaysia.

“ Thousands of ceramic shards were excavated in 1949 under the curatorship Tom Harrison. Other than Chinese ceramics, about 40,000 tons of iron slag formed another salient discovery. It is believed that this area was once an important centre of traders and iron mining in the region between 11th century A.D. to 13th century A.D.”

4.One of the earliest censuses recorded there logged 8000 people living in the entire Sarawak river basin in 1839.

They were mostly Dayaks with perhaps 1,500 to 2,000 Malays and a few Chinese.

5.There were Dayak who settled in Padungan

Speaking of the Dayaks, columnist Sidi Munan once highlighted the existence of Iban settlers in Padungan before the arrival of James Brooke in his 2019 column in The Borneo Post:

“I didn’t know about all this until I read an account of the early missionaries. The Rev William Henry Gomes had been working in the Mission station in Lundu. On Dec 24, 1859, while resting in Kuching, he wrote to his boss in London talking about the Dayaks of Padungan. Beautiful handwriting the Rev had, I’ve seen copies of some of his correspondence. He was familiar with the longhouse at Padungan, and must have visited it at least a few times.”

The ‘firsts’ in the History of Kuching

6.The ‘first’ library of Sarawak was burnt down during the Bau Rebellion.

It was perhaps Sarawak’s first library, although it was never officially announced as one. James Brooke had a library in his house in which he allowed his fellow European residents to use. Unfortunately, everything was burnt down during the Bau Rebellion.

Harriette McDougall in her book Sketches of Our Life at Sarawak described the incident.

“And then the library! a treasure indeed in the jungle; books on all sorts of subjects, bound in enticing covers, always inviting you to bodily repose and mental activity or amusement, as you might prefer. This library, so dear to us all because we were all allowed to share it, was burnt in 1857 by the Chinese rebels. It took two days to burn. I watched it from our library over the water, and saw the mass of books glowing dull red like a furnace, long after the flames had consumed the wooden house. It made one’s heart ache to see it.”

7.The first Chinese settlers called Main Bazaar road as Hai Chun Street (meaning lips of the sea).

According to International Times, Chinese settlers usually named the first street near river as Hai Gan Street which means ‘at the edge of river or sea’.

This is because the early transportation in Southeast Asia were heavily dependent on rivers.

When the Chinese first came to Kuching, they named the first street in Kuching as Hai Chun Street instead. The name can be translated as lip of the sea.

Today, it is more popular known as Main Bazaar Road and it is known to be the oldest street in Kuching.

8.The oldest temple in Kuching city is the Tua Pek Kong Temple, Kuching

Also known as Siew San Teng Temple, Tua Pek Kong Temple is a Chinese Temple situated near Kuching Waterfront.

Although its history can be traced back to 1843, it is believed to had been in existence before 1839.

9.The oldest mosque in Kuching is also the oldest mosque in Sarawak.

The mosque was built in 1847 by Datu Patinggi Ali and his family. In the beginning, the structure was simple and made from wood. When cement was imported in Sarawak in 1880, the mosque was reinforced using bricks and concrete. The first imam was Datu Patinggi Abdul Gapur who was the son in-law of Datu Patinggi Ali.

10.The courtyard at Fort Margherita was used as an execution ground.

Built in 1879, the position of the fort was carefully chosen to defend Kuching from possible attacks.

While it is beautiful from the outside, Fort Margherita carries a dark secret on the inside.

The courtyard reportedly was used to execute prisoners right up to the Japanese occupation during World War II.

11.The Square Tower was a dancing hall at one point.

Lucas Chin in his paper Cultural Heritage of Sarawak pointed out that the tower was built for the detention of prisoners and later used as a fort and dancing hall during the Brooke era.

An impressive building filled with past stories of prisoners and dancers since 1879, it has now become a mere restaurant.

12.The Astana hosted fancy balls every now and then during the Brooke administration.

While the Square Tower had its role as a dancing hall, the Astana witnessed its own fair share of fun during the Brooke era.

Former Brooke officer John Beville Archer recalled in his book ‘Glimpses of Sarawak between 1912 and 1946’,

“Now and again there was a fancy dress ball at the Astana. Ingenuity in thinking out and making fancy dresses will never cease, but I remember two cases in which realism to do the thing properly overcame prudence. One gentleman, desiring to go as a Dayak, had himself painted all over with iodine. The result of course was a bed in the hospital. The other was the cases which the guest insisted on going as a Negro – he spent days in experimenting with dyes and pigments until he thought he had the right mixture. It certainly was a triumph of make up but it did not please his little wife at all. For days afterwards suspicious smears disfigured her face. The would-be Negro was eventually given a few days leave to become a pale-face again.”

Once known as the Government House, the Astana was built by Charles Brooke as a gift to his wife Margaret.

13.The Round Tower was originally planned to built as a fort.

According to Chang Pat Foh in the book Legend and History of Sarawak, the Round Tower was planned as a fort but never fully completed.

It was used as a dispensary for a while and later it was used by the Labour Department.

14.Kuching’s first ever hotel was the Rajah’s Arm.

It was first opened on Dec 1, 1872. The hotel was mentioned in a book by American taxidermist and author, William Temple Hornaday.

The Man Who Became A Savage: A Story of Our Own Times (1896) is a fictional account of how a man became a headhunter in Borneo.

In the book, Hornaday described the hotel as a ‘comfortable lodgment’ but with an ‘indifferent cook’.

Hornaday visited Southeast Asia including Singapore, Malaya and Sarawak in 1878 and stayed at the Rajah’s Arm Hotel during his visit in Kuching.

15.The first church bell of St. Thomas church was cast by a Javanese from broken gongs.

Harriette McDougall in her book Sketches of Our Life At Sarawak explained how the church bell was made.

“The church bell was a difficult matter. Nothing larger than a ship bell could be found in the straits. At last, a Javanese at Sarawak said he could cast a bell large enough if he had the metal; so Frank (Bishop Frank McDougall) bought a hundredweight of broken gong – there is a great deal of silver in gong metal – and with these the bell was cast. Then an inscription had to be put round the rim – “Gloria in excelsis Deo,” in large letters; and the date, Sir James Brooke’s name on one side and F.T. McDougall on the other.”

16.The first Malay house in Kuching to be built using stones and concrete was the Rumah Warisan Datuk Bandar Abang Haji Kassim located at Jalan Datuk Ajibah Abol, Kampung Masjid.

Built in 1863 by Kuching mayor Datuk Bandar Abang Haji Kassim, this was the biggest palatial size Malay house in town at that time.

Since it was the first Malay house built using stones and concretes, the locals called it ‘Rumah Batu’.

Kassim died in Mecca in 1921. His son Datu Patinggi Abang Haji Abdillah was a prominent community leader known for his protest against the cession of Sarawak to the British Empire.

17.The first Roman Catholic school in Kuching, St Joseph’s School only had 20 students when they first started.

When the first group of Mill Hill Fathers came to Sarawak in 1881, they realised there were not many formal school in Kuching.

The following year in April in 1882, the priests started a school catering for children regardless of their racial backgrounds.

They named it St Joseph’s School after the patron of the Mill Hill Fathers.

When they first started, there were only 20 boys studying there.

18.In 1921, Kuching’s Roman Catholic Parish owned at least 30 acres of rubbers as a means of support.

The Roman Catholic Mission in Sarawak began in 1881, Fathers Edmund Dunn, Aloysius Goosens and David Kilty from the Mill Hill Mission arrived in Kuching from London.

When they first arrived on the afternoon of July 10, 1881, they were met by the private secretary of Rajah Charles Brooke who arranged them to live in the hotel.

In the paper ‘A History of the Catholic Church in East Malaysia and Brunei (1880-1976)’, John Rooney described what happened when the priests first arrived.

“The Rajah had set aside ten acres of land for the use of the mission in Kuching but he suggested that its main efforts should be directed to Upper Sarawak and the Rejang. The site granted by the Rajah was a very fine one and had already been cleared by jungle but there were no buildings on it and the Fathers, worried about the costs of a long stay at the hotel, asked for the temporary loan of a government bungalow until such time as proper accommodation could be provided. The Rajah agreed to this request, but he suggested they should first pay a visit to the Rejang and arranged for them to make the trip in his own yacht. On they return to Kuching a fortnight later, they discovered that the Ranee Margaret had already furnished the bungalow for them and they were able to settle very quickly into their new home.”

During the early days of the missionary, funds were limited.

Msgr. Dunn, who was the Apostolic Prefects of Sarawak (1927-1935), encouraged each mission to plant rubber gardens to raise funds.

By 1921, Kuching mission owned 30 acres of rubbers while Kanowit 40 acres, Sibu 27 acres and the Baram mission 30 acres.

19.The first rubber trees planted in Sarawak was at the Anglican bishop’s garden in Kuching.

According to Henry Nicholas Ridley in his article which was published in the Agricultural Bulletin of the Straits Settlements in 1905, the first rubber trees in Sarawak was planted by Bishop George Frederick Hose at his garden.

He brought them over from Singapore’s Botanic Garden in 1881.

20.The first Gurdwara Sahib in Sarawak was built with all Sikhs in Kuching had to contribute at least one month’s salary towards the building funds.

According to history, the Sikh community in Kuching decided to build a Gurdwara Sahib on Oct 1, 1910.

The government agreed to contribute 0.37 acres to serve this purpose.

As for the building fund, all Sikhs in Kuching were made mandatory to contribute at least one month’s salary.

The double storey wooden building was finally open on Oct 1, 1912.

Then this building was demolished to make way for the new golden-domed temple in 1982.

21.Kuching Central Prison was older than Kuala Lumpur’s Pudu Prison.

Kuching Central Prison was built in 1882 while Pudu Prison was built in phases by the British between 1891 and 1895.

Kuching’s prison was demolished in 2010. By December 2012, all buildings within the Pudu Prison complex were completely demolished.

22.The Sarawak Club was first established as a public club and an accommodation house.

Being established in 1876, the club is now one of the oldest private membership clubs in Malaysia.

However, the Sarawak Club used to be both a club and a lodging house.

“The Club, a comfortable stone building, was founded by the Government a few years ago, and contains bedrooms for the use of outstation officers when on a visit to Kuching. A lawn-tennis ground and bowling alley are attached to it, and serve to kill the time,” Harry de Windt wrote in his book On the Equator (1882).

23.There was a ladies club which was located at the corner of Khoo Hun Yeang Street and Barrack Road.

Archer in his book pointed out that the club in those days was very masculine, stating “rather in the style of the famous notice in the Jesselton Club ‘No dogs or women admitted’”.

Hence, the very few women of Kuching formed a club on their own in 1896.

They even had a place to play croquet. Then in 1908, the building was demolished to make way for the Government Printing Office.

Then the ladies was given another club house; between back then Aurora Chambers and Sarawak Museum.

24.Kuching is the second town in Malaysia to have urban water supply after Penang.

When two small lakes were dug out in 1895 to serve as reservoirs, Kuching became the second town in Malaysia to have piped water supply after Penang.

According to Ho Ah Chon in his book Kuching in Pictures 1841-1946, before this all water had to be carried by the tukang ayer (water carrier) in kerosine tins from the nearest little stream before.

The reservoirs stopped operating in the 1930s.

25.The first ice factory in Kuching was opened on Aug 18, 1898.

At that time, one pound of ice cost two cents to ordinary residents, and one and a half cents to ice cream vendors.

26.The first building in Sarawak to use a precast concrete floor system is the Old Government Treasury and Audit Department Building.

Completed in 1927, the building is similar to the Old Kuching Courthouse architectural-wise.

The building was later used by Bank Negara Malaysia.

27.Meanwhile, the first building in Sarawak to use reinforced concrete is the Pavilion Building.

Completed in 1909, the Pavilion Building was used as Medical Headquarters as well as hospital for the Europeans until the mid 1920s.

28.Hong Leong Bank was first started in Kuching back in 1905.

It was first registered under the name of Kwong Lee Mortgage and Remittance Company.

The company granted loan against the security of export commodities such as pepper and rubber.

29.CIMB has its origin roots in Kuching.

Bian Chiang Bank was established in Kuching by Wee Kheng Chiang in 1924. In its early days, the bank focused on business financing and the issuance of bills of exchange. It was renamed Bank of Commerce Berhad in 1979.

It is one of the various bank that formed CIMB (Commerce International Merchant Bankers).

Wee also founded United Chinese Bank in 1935. It is now known United Overseas Bank or UOB.

30.The first branch of Chartered Bank in Borneo island was opened up in Kuching back in 1924.

The Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China established its first branch in Malaysia on Beach Street, Penang in 1875. Today, it is the oldest branch of any bank in Malaysia.

Then in 1888, they opened another branch on Jalan Raja, Kuala Lumpur.

When the bank opened its branch in Kuching in 1924, it was their first branch on Borneo island.

In 1985, the Chartered Bank in Malaysia changed its name to Standard Chartered Bank that we know today.

31.The first wireless station was installed in 1916.

The first wireless station in Kuching was established when two large steel pylons were put up not far from St. Joseph’s School.

Then, the first messages were transmitted from Kuching to Penang and Singapore on Oct 25, 1916.

32.The first Kuching Airport was only consisted of two grass-surfaced runways, each 800 yards long.

The airfield was officially opened on Sept 26, 1938. When the Japanese invaded Kuching, the runways were slightly destroyed. Although the Japanese rebuilt them, the airfield was destroyed by Australian bombing.

33.Bako National Park is the oldest national park in Sarawak and the second oldest in Malaysia.

Established in 1957, Bako National Park covers an area of 27.27 square kilometers at the top of the Muara Tebas peninsula at the mouth of the Bako and Kuching Rivers.

However, the area has been a reserve since 1927 when it was formerly known as Muara Tebas Forest Reserve.

Before this, these places in Kuching were…

34.Jalan Taman Budaya was originally named Pearse’s Road.

The road first named after Charles Samuel Pearse who worked in the Treasury. He joined Sarawak Service as a cadet on July 5, 1875 and later appointed cashier on Sept 1 the same year. He was appointed as Treasurer on May 1, 1877. Pearce retired on pension on 1898 and passed away in 1911.

35.Jalan Stephen Yong was originally named Jalan Wee Hood Teck.

From 1968 to 1973, the road was named Jalan Wee Hood Teck. He was the son of United Overseas Bank founder Wee Kheng Chiang.

It was later renamed as Jalan Stephen Yong after Tan Sri Datuk Amar Stephen Yong Kuet Tze. He was a former Malaysian cabinet minister.

36.Kuching High School was first known Min Teck Middle School.

The school was founded in 1916 by Kuching Teochew Association as Min Teck Junior Middle School.

37.Kai Joo Lane was known as sa lee hung or lane of zinc sheets in Teochew or Hokkien.

According to a report by The Borneo Post, the two rows of 32 shops along Kai Joo Lane were built by a Teochew businessman named Teo Kai Joo (1870-1924) in 1923.

When these shops were first built, the buildings were made of red-brown bricks with zinc sheet roofing. Hence, the name sar lee hung.

38.The site of Kuching’s Open Air Market was a reclaimed tidal creek.

While most people often referred it as Open Air Market, the building is in fact named Tower Market.

It derived its name from the remnant tower belonging to the Old Kuching Fire Station.

Even before there was a fire station, there was small creek named Sungai Gartak flowed through the area.

The creek was reclaimed in 1899.

The road Jalan Gartak was named after it.

39.The site of Old General Post Office building was once served as a police station and Rajah’s stable.

Built in 1931, the majestic building which served as a post office was designed by Singapore’s Messr. Swan & Maclaren Architects.

Swan & Maclaren were responsible of designing many Singapore’s historical buildings including Raffles Hotel (1899) and Saint Joseph’s Cathedral (1912).

Before this, the site was a police station and Rajah’s stables.

40.Padang Merdeka was once called ‘The Esplanade’.

According to John Ting in his paper Colonialism and the Brooke Administration Institutional Buildings and Infrastructure in 19th Century Sarawak, the area was established in 1920.

“It was originally reclaimed from swampy land and configured as a municipal park called ‘The Esplanade’. The rectangular park had paths that ran diagonally from the corners and a bandstand. The bandstand’s location made it in appropriate for parades and it was demolished when Sarawak became a colony,” Ting stated.

41.The site of Kuching Old Courthouse once stood a Lutheran church building.

A reverend named Father Rupe from the German Lutheran Communion built a two-storey wooden building on the site in 1847.

He planned to have the ground floor as a place of worship while he lived in the upper floor.

Just right after the building was finished, Rupe returned back to Germany.

James Brooke took over the building then and turned it into a hall for the administration of justice.

The remains of the brick steps of Rupe’s original building is still under the floorboard.

Kuching during and after Japanese Occupation

42.During WWII, the first Allied submarine in Pacific to sink a warship was the Royal Netherlands Navy HNLMS K XVI and the incident took place in Kuching.

On Christmas Eve 1941 about 65km off Kuching, the submarine torpedoed and sank the Japanese destroyer Sagiri.

The destroyer’s aft magazine caught was fire and exploded sinking the ship with 121 of the 241 personnel aboard killed.

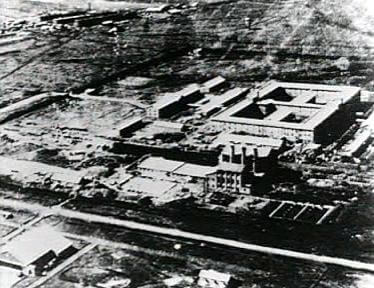

43.Batu Lintang Camp was unusual because it housed both Allied prisoners of war (POWs) and civilian internees.

Operated from March 1942 until the liberation of the camp in September 1945, the site was originally British Indian Army barracks.

44.St Thomas School was used as a labour camp.

The Japanese reportedly even tried to built a swimming pool there but it was never completed.

45.There were four military brothels in Kuching during the Japanese occupation.

According to Ooi Keat Gin in the book the Japanese Occupation of Borneo 1941-1945, these four locations were Borneo Company Limited manager’s bungalow, Chung Wah School Pig Lane (now Park Lane), St Mary’s School Hostel and Chan’s family mansion at Tabuan Road.

The inmates of these brothels were Korean, Japanese as well as Javanese.

46.Yokohama Specie Bank opened a branch in Kuching during the occupation in early 1942 in the former building of Chartered Bank.

The Yokohama Specie bank was a Japanese bank founded in Yokohama, Japan in the year 1880.

After the end of WWII in 1946, its assets were transferred to The Bank of Tokyo. Naturally, the branch in Kuching closed down after the war had ended.

47.The Sarawak Museum thankfully suffered little damage during the war because the Japanese official in charge.

In the book ‘Glimpses of Sarawak between 1912 and 1946’, John Beville Archer recounted what took place after WWII.

“At first, I was given the Sarawak Museum office and become involved in listening to all sorts of requests and appeals. One of duties was trying to collect what I could of the Rajah’s property. Strange enough, the Japanese had done no damage to the Astana and its contents were almost intact but scattered. For instance, I managed to find the Rajah’s insignia, the State Sword and other relics. The Museum lost very little; this was because the Japanese official in charge of it for the last two years was, it is said, an Oxford University graduate.”

48.Darul Kurnia was the site where anti-cession movement protesters demonstrated against ‘Circular No.9’.

After the war ended, many joined Datu Patinggi Abang Haji Abdillah and Datu Patinggi Haji Kassim to fight against cession of Sarawak to Britain.

After realising that most of the members of the movement were civil servants, the colonial office issued ‘Circular No.9’ on Dec 31, 1946.

The circular warned civil servants that it was illegal to join in political movements.

The peak of the anti-cession movement took place on Apr 2, 1947 when 338 civil servants submitted their resignation letters.

On the same day, they all stood on the ground of Darul Kurnia to show their protest.

Located at Jalan Haji Taha, Darul Kurnia is a colonial style mansion built in the 1930s by Datu Patinggi Abang Haji Abdillah.

49.There are at least five war and hero memorials in Kuching.

These memorials include the Clock Tower at Jalan Padungan, the Sarawak Volunteer Mechanics and Drivers at Tabuan Laru, Heroes Monument at Sarawak Museum ground, World War II Herous Grave at Jalan Taman Budaya and Batu Lintang Camp Memorial at the Batu Lintang Teacher’s Education Institute.

50.Fort Margherita has flown four different flags under four different administrations.

The first flag was of course Brookes’ Sarawak flag, then the Rising Sun during WWII.

When the state became a crown colony, it was the Union Jack and now our very own Sarawak flag.