The Battle of Long Jawai was one of the earliest battles in the history of the Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation (1963-1966).

Indonesia’s then President Sukarno opposed the new nation arguing it was a British puppet state and a new-colonial experiment.

Additionally, they claimed if there was any expansion of Malaysia, it would increase British control over the region while possibly implicating Indonesia’s national security.

Meanwhile, the Philippines opposed the federation as they made a claim on eastern North Borneo for its historical links with the Sulu archipelago.

Initially, the Malayan government had set Aug 31, 1963 as the date on which Malaysia would come into existence.

This was to coincide with Malaya’s independence day celebration.

However, due to fierce opposition from the Indonesian and Philippine governments, the date was postponed.

Both countries later agreed they would accept the formation of Malaysia if a majority in North Borneo and Sarawak voted for it in a referendum organised by the United Nations.

But amidst these peace talks and the referendum, Indonesia had already started their infiltration into Sarawak through Kalimantan.

On Aug 15, 1963, there was an incursion into the Third Division (what is Sibu Division today). Then Gurkha soldiers were deployed to the border there to patrol and ambush incursions.

After a month of operations, 15 of the enemy forces had been killed and three were captured.

This was not the last of the incursion by the Indonesian army.

The Battle of Long Jawai

Less than two weeks after the Malaysian federation was declared on Sept 16, another incursion happened in a small outpost in Long Jawai of Third Division, about 30 miles from the Sarawak border.

Long Jawai back then was a small settlement with a population of 500 and the outpost was also used by the Japanese troops during World War II.

On the morning of Sept 28, about 150 (some records state 200) Indonesian soldiers attacked the outpost.

The outpost was garrisoned by six Gurkha soldiers led by Corporal Tejbahadur Gurung, three policemen and 21 Sarawak border scouts.

In Britain’s Brigade of Gurkhas by E.D. Smith, the men at the outpost were reported still sleeping when they were first attacked.

“At about half-past five the Gurkha rifleman on sentry duty heard movement near his post. Every man stood to. Shortly afterwards, three or four shots were fired nearby,” Smith wrote.

Another account pointed out that a border scout left his position to visit his sick wife in the village.

There in the village, he spotted some Indonesian soldiers and raced back to warn his comrades.

Regardless, Corporal Gurung quickly alerted the radio operators in their signal hut to establish communication with their headquarters.

Soon enough, the Indonesians launched their attacks.

They blasted the outpost with mortar bombs, machine guns and heavy small-arms fire.

Meanwhile, a small party of the enemy charged into the signal hut where the radio operators were still trying to contact their headquarters.

Unaware that their enemies were approaching since they were wearing earphones, the operators were killed before any communication was established.

The retreat to Belaga

In the meantime, the two sides of the battle continued to exchange fire until the fighting lasted for a few hours.

By 8am, only three men were left and able to continue to fight while the rest were wounded. This was when Corporal Gurung decided to call a retreat.

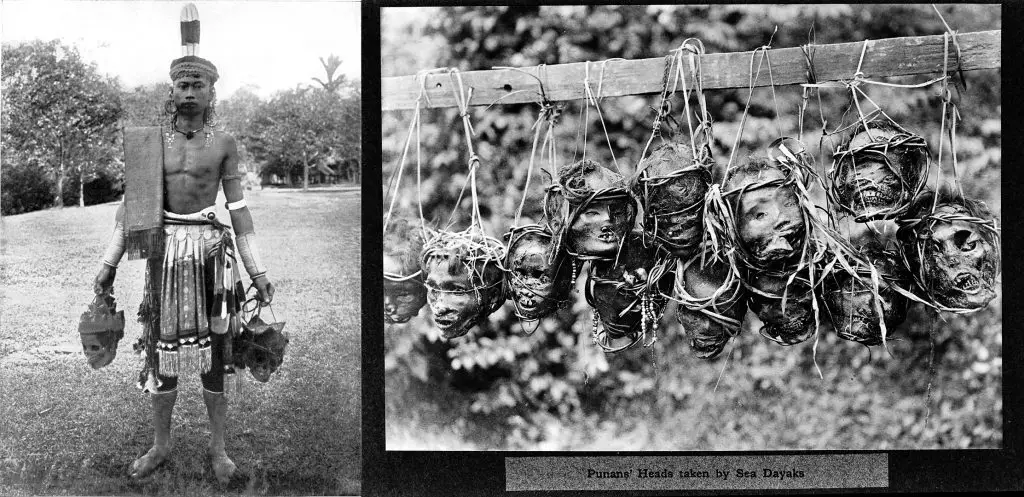

Unfortunately for the local scouts, all but one were captured by the Indonesian armies. Ten (some accounts stated eight) of the scouts were later executed.

The only scout who managed to escape went along with Corporal Gurung and the remaining Gurkha soldiers searching for safety.

Smith described their journey in his book, “Without food or medical supplies the small party spent the night in pouring rain, keeping the wounded men as warm as they could. Then, having made them as comfortable as possible, the corporal and his companions left for the nearest village, many miles away. Living off roots, they had a long and hazardous journey as it was four days before they reached the outpost of Belaga, weak and exhausted but with weapons spotlessly clean and able to give first-hand account of the battle.”

The aftermath of Battle of Long Jawai

At this time the Malaysian federation had come into existence. So by attacking Long Jawai, Indonesia had broken off its diplomatic relations with Malaysia.

In response, other Gurkha units were deployed into the air using helicopters. They began attacking any stragglers and small units broken off from the main force.

Eventually, they also found the tortured bodies of the local scouts.

On Oct 1, the Gurkha units caught two longboats carrying the Indonesian armies in an ambush eventually killing 26 of them.

The Indonesian survivors of this attack were later then killed in another ambush on Oct 10.

Overall, the Battle of Long Jawai had cost the lives of many from both sides. Thirty three Indonesians were killed while 13 British and Malaysian soldiers died during the battle.

Long Jawai or Long Jawe or Long Jawi or Long Jawe’?

If you can’t find Long Jawai in a Sarawak map, that is because it is spelt differently in different records.

Most non-Malaysian books and records spelt it as Long Jawai. Other records spell it as Long Jawe, Long Jawi or Long Jawe’.

All of these names refer to a large but isolated Kenyah longhouse far up the Balui tributary of the Rejang.

After the confrontation, former Sarawak Information Services Director Alastair Morrison visited Long Jawai with Temenggong Jugah Barieng when the latter was holding the post of Minister for Sarawak Affairs.

According to Morrison, the visit was to make relief payments to the relatives of those killed during the Battle of Long Jawai.

He wrote in his book Fair Land Sarawak, “The people of Long Jawi had only moved into Sarawak during the war and they had been much upset by the attack made on them. Their assailants had suffered severely because troops had been flown in behind them and they were ambushed on their return journey, but this did not save the border scouts who had been captured. They were taken a little way upriver and there slaughtered- apparently a return to an old and blood thirsty ritual.”

The residents of Long Jawai were very welcoming of Morrison and Jugah during their visit.

Morrison described his experience, “My special recollections of Long Jawi were Jugah addressing the people of the longhouse later, when we were entertained in the traditional manner, dancing the ngajat of seeing the wall behind him festooned with pictures of the British Royal Family. And, of course, the young 6th Gurkhas then garrisoning the area. Several off-duty soldiers attended the presentation and subsequent party. They were called on to dance and replied that as good soldiers they could not possibly do anything like that. They gave demonstration of arms drill instead. But as the evening wore on it became apparent that not only had they been dancing in Long Jawi, but that they had been teaching the Kenyah girls Nepalese dances too.”

A historical site wiped out in the name of development

Although Long Jawai played an important historical site for Sarawak and Commonwealth countries overall, there is no remnant of it today.

This is because the area became submerged underwater when the Bakun dam impoundment began in 2010.