Do you know that a severe chronic form of thiamine (vitamin B1) is known as beriberi?

The term ‘beriberi’ is believed to come from a Sinhalese phrase for ‘weak, weak’ or ‘I cannot, I cannot’.

There are two main types in adults; wet beriberi and dry beriberi. Wet beriberi affects the cardiovascular system while the dry beriberi affects the nervous system.

During World War II, beriberi was widespread among Allied prisoners of war (POWs) captured by the Japanese.

This is due to they were fed only with a diet of rice which did not contain adequate quantities of most vitamins.

Beriberi’s symptoms among POWs

When suffering from dry beriberi, the victims would experience tingling in their hands and feet, loss of muscle function, vomiting and mental confusion.

Meanwhile, suffering from wet beriberi commonly can cause oedema or severe swelling. Another Australian POW Stan Arneil recalled what was it like to suffer from oedema due to beriberi.

“The symptoms were swollen feet and legs as the moisture contained in the body flowed down towards the feet. Ankles disappeared altogether and left two large feet almost like loaves of bread from which sprouted legs like small tree trunks, in bad cases the neck swelled also so that the head seemed to be part of the shoulders.”

Despite this, the Japanese continued to force the POWs to work through their sickness as no medical care was given.

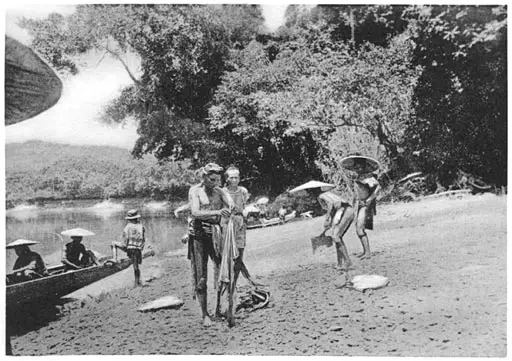

During the Sandakan Death Marches for instance, POWs were forced to march from Sandakan to Ranau, of a distance of approximately 260km long through thick tropical jungle.

Those who too weak to walk due to exhaustion or sickness, were shot by Japanese guard.

“Death had slippers” when it came to beriberi

Speaking of Sandakan Death Marches, an Australian POW who had a very narrow escape from the deadly march witnessed first hand how a victim of beriberi perished.

Billy Young was among the soldiers who was imprisoned at Sandakan POW Camp.

After a failed escape from the camp, he was sent to Outram Road Jail in Singapore. This turned out to be a blessing in disguise for Young as those who stayed at Sandakan camp all died during the war (except for six Australians who managed to escape).

Still, Young went through hell on earth where he spent six months in solitary confinement and was forced to sit cross legged for hours at a time.

Since food rations were scarce, everyone including Young became skeletal. One time, one of Young’s inmates, a Dutch, died in his arms due to beriberi.

“I put his head on my lap. I chatted to him and I pushed his chest and felt it. And you could feel it going up and down as he was panting for breath. But death must have had slippers because he died and I didn’t know so I waited.

“I put him down and I didn’t tell the guard, and I waited till his box of rice came and I put Peter’s bowl by him. And I got mine, I ate mine, and then I ate Peter’s. And that’s the only banquet we ever had between us you know.”

Similarly, many of the surviving POWs described the deaths of the fellow comrades due to beriberi as ‘wasting away’.

Beriberi, a ‘norm’ for Prisoners of War

Ian Duncan was one of thousands Australian POWs who were send to work at Burma-Thai Railway.

He once shared this to journalist Tim Bowden during an interview, “At the end of the war, I interviewed every Australian and English soldier in my camp. I was the only medical officer in the camp. And I though it was duty to record their disabilities. And you’d say to them, what diseases did you have as a prisoner of war? Nothing much, Doc, nothing much at all. Did you have malaria? Oh yes, I had malaria. Did you have dysentery? Oh yes, I had dysentery. Did you have beriberi? Yes, I had beriberi. Did you have pellagra? Yes, I had pellagra but nothing very much. These are lethal diseases. But that was the norm, you see, everyone had them. Therefore they accepted them as normal.”

Burma-Thai POW camp was not the only one which was suffering from this disease. Another infamous Japanese internment camp is Batu Lintang Camp in Kuching which had similar conditions.

After the camp was liberated on Aug 30, 1945, a female civilian internee who was also a nurse named Hilda Bates went to visit the sick POWs.

She recounted, “I was horrified to see the condition of some of the men. I was pretty well hardened to sickness, dirt and disease, but never had I seen anything like this in all my years of nursing. Pictures of hospital during the Crimean War showed terrible conditions, but even those could not compare with the dreadful sights I met on this visit. Shells of men lay on the floor sunken-eyed and helpless; some were swollen with hunger, oedema and beriberi, others in the last stages of dysentery, lay unconscious and dying.”

Meanwhile in Indonesia, it was reported the disease affected nearly one hundred percent of Bataan POWs. It was considered as the most ubiquitous disease among the POWs.

Experiments on POWs to cure beriberi

A Japanese doctor army named Masao Mizuno described experiments he conducted in a report he submitted in October 1943.

He wrote in the report, “In South Sea operations, such conditions as the lack of materials, the difficulty in sending war materials, the heat and moisture, increase the occurrence of beriberi patients. For this reasons, attention must be given to the use of local products. Favourable results in the prevention of beriberi have been noticed by the usage of coconut milk, coconut meat and the yeast from corn.”

Mizuno continued to describe an experimental treatment he did on 16 POWs who were suffering from beriberi in an unknown location.

He gave them hypodermic injections of 30ml of sterilized coconut milk. (Yes, you read that right – sterilized coconut milk.)

According to Mizuno, most patients felt a slight prickling pressure pain at the site of the first injection and one felt a slight headache.

Later, the condition of most patients improved with the second, third and fourth injections. They showed ‘satisfactory pulse, refreshing sensation and increased appetite.’

However, it is not known whether these experiments were continued or if the procedure was ever used as a treatment.

The death tolls caused by beriberi among Allied POWs remain unknown

Through survivors’ testimonies, we might know which perished Allied POWs had the disease but we will never if the disease was the leading cause of death.

Just like Dr Duncan had testified, these poor men had other diseases such as pellagra, malaria, dysentery on top of beriberi.

For the fortunate POWs who were freed after the war had ended, sickness including beriberi followed them into their liberation.

It was reported that some deaths due to wet beriberi did occur soon after their release but the number was small and did not continue.

One unusual case, however, did happened on a British POW who died of cardiac failure 31 years after his release.

As a POW, he suffered very severe beriberi. After autopsy, it was found that he had extensive myocardial fibrosis considered due to the effects of severe wet beriberi.

Unfortunately until today, it is difficult to know how many Allied POWs suffered or died due to beriberi during and after the war.