Have you every wondered what life was like in Sarawak over a hundred years ago?

Thanks to a contributing writer of The Sarawak Gazette in 1948 who wrote under the initials ‘O.F’, we had a glimpse of old Sarawak through his writing.

So here is the author’s account of what it was like living in Sarawak in 1912:

“Sarawak in 1912 was enjoying the end of its heydays. The last great war had been the affair in South Africa, and bar a Melanau policeman we all called Lord Kitchener on account of his moustache, and a gentleman who after a gin or two loved telling us about the joys of the Base at Cape Town, that campaign had left no visible mark on the country.

Cadets came out on a hundred dollars a month and the five years furlough was a thing recent memory. One of my first outstation acquaintances was just about to go home after a full ten years service. He looked extremely healthy and I am certain that he did not have an electrolux either.

The whole European Civil Service numbered less than fifty, of which about twenty one were in outstations, the same number in Kuching and the rest or knocking about somewhere. Except for the staff of the two Government collieries there were no Departmental officers outside Kuching.

There was no wireless, no electric light (except, I think, in Bau) but one motorcar, no buses, no cocktail parties and no slap-and-tickle dancing.

Those ladies who wore European dress would not have been seen dead in the street without a monster hat or topi; those who wore Malay dress covered their shy heads with gay sarongs and veils; only the older Chinese women were ever seen in public.

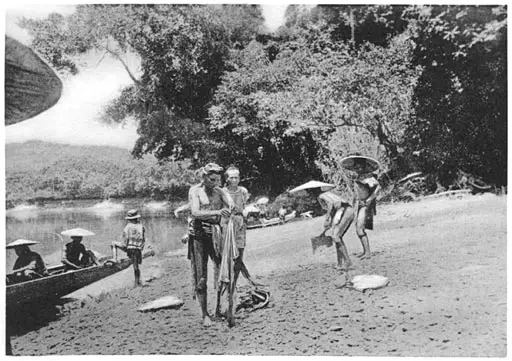

Lofty masted schooners lay in the creek off Sibu Maleng. The Second Division was served by sailing bandongs, propelled up the rivers by the crew sweating at the sweeps; steam vessels and launches laboriously pounded along with sparks sometimes flying from the funnel from the wood fuel.

In Kuching Lee Wai Heng made us good white suits for three dollars sixty and a khaki one was four dollars and a half. Hap Shin would make white canvas shoes for a dollar twenty. Syn Hin Leong, Chong Kim Eng and Ban Jui Long had good whisky at under a dollar a bottle for the same sum you could get nearly three tins of cigarettes. If you went the right way about it it was possible to charter a smart rickshaw to take you to and from the office every day, and a few odd extra trips thrown in, for fifteen dollars a month you could send all the washing you liked to a dhobie for a monthly payment of four dollars.

Sebah, known to everyone, brought round real kain tenun for a couple of dollars a piece, and she was a pleasant company too. Good gold, as pure as one could wish for, could be bought over the counter from Kong Chan for a bit over four and a half dollars an amas, real gold sovereigns about nine dollars, half a quid for four fifty and a real whopper of an American gold piece for about seventeen dollars. Belts made of silver dollars cost their face value plus an equal amount for labour. Every year the pawn farmers used to melt down the unredeemed gold, and I have handled lumps of the stuff.

In Singapore the police arrested Sarawak Dayaks for walking around Raffles Place in a chawat, cables were received from England and Singapore via Labuan, the festival of chap goh meh was the only time one saw Chinese girls, and the idea of ‘Women’s Day’ or processions of gaily clad members of Kaum Ibu was a thing which no man, brown, yellow or white, could dream of.

Once a year, hordes of little Malay boys went over to the Astana to eat the Rajah’s curry, and on New Year’s Day there was a monster regatta. Tuba fishing were always great occasions. In outstations everyone nearby took a holiday. Government servants included, and even if the catches were hot often great the fun was. Most of the tuba was secreted for private fishing up small streams the next day.

In Limbang they raced buffaloes, and in Sibu we spent half the landas roaming about in small boats. When the officers in Mukah and Oya got bored they went pukat fishing with the police and prisoners. In Bintulu they went to Kedurong (Kidurong) to catch rock cod and cast a jala.

Sarawak Rangers paraded with snider rifles and sword bayonets; at headquarters they still exercised in ‘form hollow square to receive cavalry!’ The Rajah’s yacht ‘Zalora’ lay off Kuching with a three-pounder hotchkiss mounted on the forecastle.

Up in the outstations administrators and people lived a feudal but by no means an uncolourful life. Now and again a headhunting foray lived up things, occasionally Chinese gang robbers threw pepper in travelers’ eyes and got away with the spoils. A sporting District Officer, out after snipe, was gored by an angry buffalo. In Limbang an unhappy Chinese tried to commit hara kiri and was saved and lived happily ever after by the efforts of the Resident and his assistant who pushed in his entrails, sewed him up and then gave him a good shaking to get them into place.

One or two small motor boats were introduced at this time and the Malays, ever quick to catch on to a good nickname, called them by a most expressive word. Rajah Brooke drove around Kuching in a wagonette, or sometimes a governess cart; the manager of the Borneo Company had a dashing dog cart. Silk-hatted gentlemen went to Church on Sunday evenings and bottle-green tails appeared at Astana functions.

No one seemed to have much money; in any cases few of the merchants seemed to use it. For raw sago the Kuching towkays sent up cargoes of tobacco, cloth, pots and pans, hurricane lamps, braces and sock suspenders and Dr Williams Pink Pills.

The State was not run on orthodox lines, and I suppose that some modern thinkers would say that it was sheer autocracy, oligarchy and despotic benevolence, and of course so it was. It was run very well. But it could not have gone on much longer. The first world war shook it a bit but left the foundations cracked but standing. The second world war finished it off.”

Curiosity for Sarawak in 1912

Obviously, there are huge changes between Sarawak in 1912 and the present.

Even though we still see ladies wearing ‘European dress’ today, they no longer pair their outfits with a ‘monster hat’.

Speaking of clothing, you will never find ‘good white suits for three dollars sixty and a khaki one for four dollars’ anywhere in this world, let alone in Kuching.

While we still have cobblers to repair our footwear, nobody would make white canvas shoes today.

Furthermore, it would be nice to have a bottle of whisky under a dollar right now.

Thanks to O.F, we now know the modus operandi of 1912 Sarawak robbers. Who knew Sarawak pepper had its criminal usage?

Plus, who knew Residents back then had the surgical skill to rescue someone who committed harakiri? Can you imagine the effort they took in 1912 to push someone’s entrails back into their abdomen and stitch them back together again?

For those who are curious, the medicine stated in the article is Dr Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People.

It contained ferrous sulfate and magnesium sulfate and it was claimed to cure chorea.You will never find it today because it was withdrawn from the market in the 1970s.

Finally, it would be interesting to know if the descendants of those O.F. mentioned in his article are still alive today