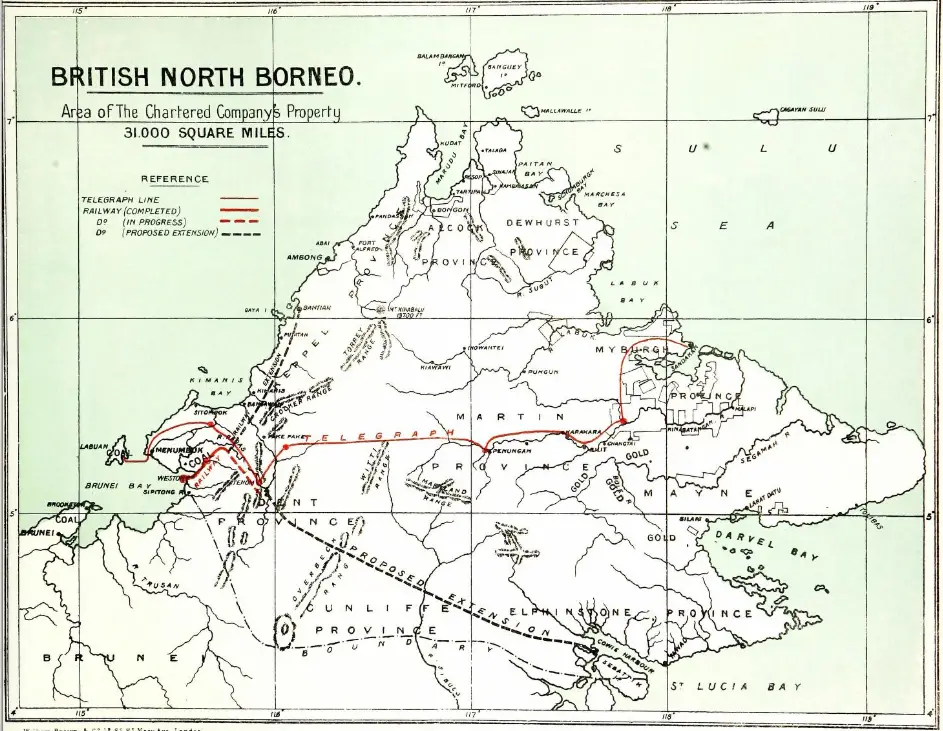

Just like Sarawak, many of North Borneo (present-day Sabah)’s territories were part of the Brunei Sultanate.

These territories were slowly annexed by the British North Borneo Chartered Company (BNBC) into the British North Borneo including Sipitang.

The people of Sipitang (Sepitong, Sipitong or Si Pitong)

So what is it like in Sipitang during those days? Owen Rutter in his book British North Borneo: an account of its history, resources and native tribes (1922) had some answers.

Describing the little town, Rutter wrote, “Sipitong, the headquarters of the district, is near the mouth of the Sipitong river, which flows into Brunei Bay. It is a lonely little station; although the district is the centre of the native sago industry it has never been developed by European enterprise, chiefly owing to the transport difficulties, an although it has been partially opened up with bridle-paths it is one of the least-known districts in the country.”

Rutter also pointed out there was Bruneians settlement found in Sipitang. While they were mainly farmers, the Bruneians were more known as boat builders. He wrote, “The Sipitong Bruneis being especially famous. They are of course immigrants pure and simple, but have firmly established themselves in the country of their adoption.”

“… they are noted in particular for the pakerangan, a canoe-shaped boat, but wide of beam and about thirty feet long, with a single square sail, or paddles for river work.”

The treaty to cede Sipitang to North Borneo Chartered Company

The annex took place on Nov 5, 1884 through an agreement between the Sultan of Brunei and BNBC.

Here are some of the contents of the treaty:

“His Highness Abdul Mumin, Sultan of Brunei and the Pangeran Bandhara and the Pangeran di Gadong for themselves, their heirs, successors and assigns hereby certify that the whole country from and including Si Pitong (Sipitang) and the whole country from and including Si Pitong and the country drained by it, on the South, to and including Kwala Paniow (Kuala Penyu) and the country drained by it, on the North, is hereby ceded to the British North Borneo Company, its successors and assigns, for so long as they choose to hold the same, as also the rivers Bangawan and Tawaran and the districts drained by them. Padas Damit is not included.”

The treaty which was signed by British North Borneo first governor William Hood Treacher from BNBC, also stated its terms.

“The Company and its representatives to pay annually to the Sultan or his heirs of $3,000 – five years’ cession money viz- fifteen thousand dollars ($15,000) being paid in advance on the completion, of this agreement of which seven thousand dollars ($7,000) shall be received in copper coin at par.”

Governor Treacher also shared about the annex in his book British Borneo: Sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan and North Borneo (1891).

“In 1884, after prolonged negotiations, I was also enable to obtain the cession of an important province on the West Coast, to the South of the original boundary, to which the name of Dent Province has been given, and which includes the Padas and Kalias rivers, and in the same deed of cession were also included two rivers which had been excepted in the first grant – the Tawaran and the Bangawan. The annual tribute under this cession is $3,100.”

BNBC’s expansion in North Borneo

While there is a little detail on what were the reasons Brunei Sultanate was willing to cede her territories to the company (besides the annual tribute paid to the Sultanate), one thing for sure; Sipitang was not the last area annexed by the BNBC.

After Sipitang, the company also acquired Mantanani (1885), Padas (1889) and Mengalong as well as Merantaman areas in 1901.

By 1901, an administrative office was set up in Sipitang called the Province Clarke, named after Lieutenant General Sir Andrew Clarke.

Today, Sipitang town is known to be the closest town in Sabah to the Sarawak border.