The name of Kanowit town comes from the earliest ethnic group who settled in the area, the Kanowits. Today, they are often referred to as Melanau Kanowit.

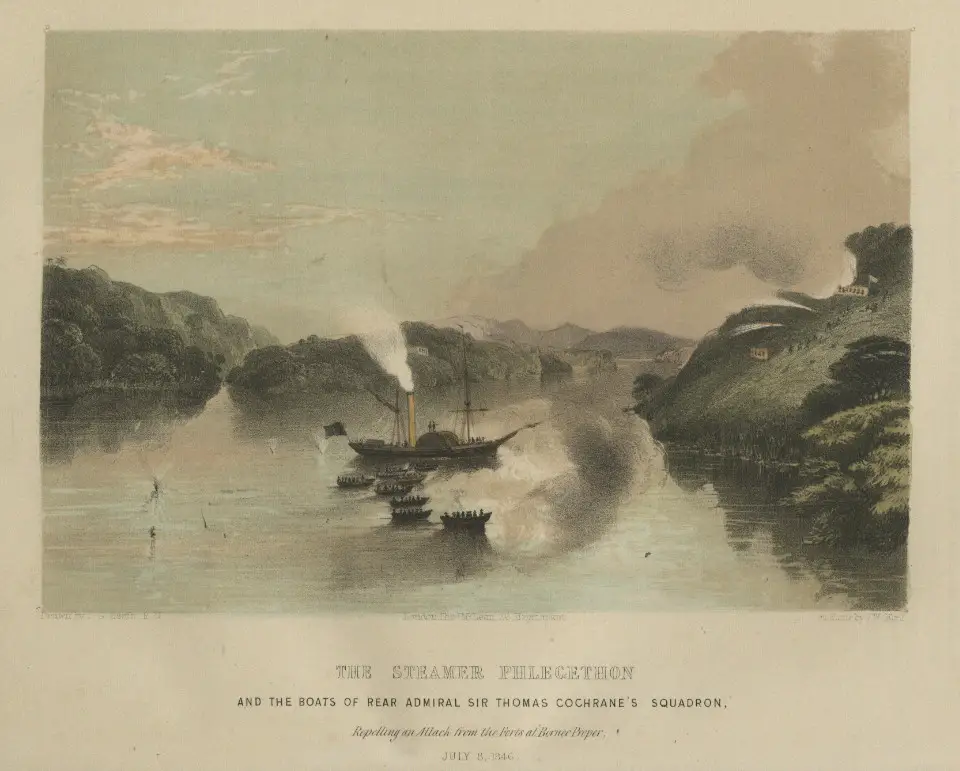

Their first contact with the British took place in 1846 when the steamer, the Phlegethon, commanded by James Brooke and Captain Rodney Mundy sailed up the Rajang River.

Brooke would have been 43 years of age at the time, and would have been Rajah of Sarawak for four years since the Sultan of Brunei had granted him the title.

On June 29, they arrived in the area that we know now as Kanowit town.

Imagine the Kanowits’ reaction watching an unfamiliar vessel came to shore with people of different skin, eye and hair colour on board… it would have been bound to create some havoc at that time.

So did their first meeting turn out a peaceful one or was there some blowpipe action going on?

The answer lies in Mundy’s journal as he describes their first encounter with the Kanowits as follows:

Shortly after noon our pilots pointed out the neck of land round which, in a small bay, was situated the village of Kanowit, and above the trees we caught sight of numerous flags, and the matted roofs of houses.

The admiral (Rajah James Brooke) now ordered the steamer to be kept as close as possible to the over-hanging palms; and with our paddle-box just grazing their feathery branches, we shot rapidly round the point, and the surprise was complete; so complete, indeed, that groups of matrons and maidens who, surrounded by numerous children, were disporting their sable forms in the silvery stream, and enjoying, under the shade of the lofty palms, its refreshing waters, had scarcely time to screen themselves from the gaze of the bold intruders on their sylvan retreat.

It would be difficult to describe the horror and consternation of these wild Dayak ladies as the anchor of the Phlegethon dropped from her bows into the centre of the little bay selected for their bathing ground.

The first impression seemed to have stupified both old and young, as they remained motionless with terror and astonishment. When conscious, however, of the terrible apparition before them, they set up a loud and simultaneous shriek, and fleeing rapidly from the water, dragged children of all ages and sizes after them, and rushed up their lofty ladders for refuge; then we heard the tom-tom beat to arms, and in every direction the warriors were observed putting on their wooden and woollen armour, and seeking their spears and sumpitans.

In ten minute all seemed ready for the fight, though evidently more anxious to find the extraordinary stranger inclined for peace. Meanwhile, the steamer swinging gradually to the young flood, and so drawing her stern within a few yards of the landing-place, brought into view the whole of the under part of the floor of this immense building erected at the very brink of the stream; for the piles on which it was supported were forty feet in height, and although at this short distance, had these savages chosen to attack us, a few of the spears and poisoned arrows might have reached our decks, it was evident that their own nest thus raised in the air, though containing 300 desperate men, was entirely at our mercy.

The chief, who was a very old man, with about thirty followers, then came on board. He was profusely tattooed all over the body, and like the rest of his savage crew, was a hideous object. The lobes of his ears hung nearly to his shoulders, and in them immense rings were fixed. Round his waist he wore a girdle of rough bark which fell below his knees, and on his ankles large rings of various metals. With the exception of the waistcloth, he was perfectly naked. We knew that this old rascal and the whole tribe were pirates downright and hereditary.

Having dismissed our visitors, we all landed and some of us mounting ladders of these extraordinary houses, presented ourselves as objects of curiosity to the women and children. I could stand upright in the room, and looking down at the scene below, might have fancied myself seated on the top-mast cross-trees. Having traversed every part of the long gallery thus level with the summits of the trees, and distributed the few gifts we had to bestow on the women and children, we turned our backs on the pendant human skulls, and retracing our steps to terra firma, immediately proceeded to the Phlegethon.

Unfortunately, the forty foot high longhouse which Brooke and Mundy visited is long gone. Additionally, we can hardly see a Kanowit man with full-bodied tattoos and long ear lobes these days.

If only the Kanowits knew how Mundy thought and described of them then, would their first encounter have been a peaceful one?