When the Malayan Peninsula and subsequently Singapore were captured during World War II (WWII), it was considered among the Japanese Army’s greatest wartime achievements.

Meanwhile, it was the worst Far Eastern defeats for Great Britain.

During WWII, Singapore was British military base in Southeast Asia.

Also known as the Fall of Singapore, the battle lasted from Feb 8 to 15, 1942.

It resulted in the Japanese capture of Singapore and the largest British surrender in history.

Here are eight things you should know about the Fall of Singapore:

1.Why did Japan attack Singapore?

According to Paul H. Kratoska in his book The Japanese Occupation of Malaya, Japan considered Malaya and Sumatra ‘the nuclear zone of the Empire’s plans for the Southern area’, and saw the Malay Peninsula as ‘the economic and communication axis for the entire Southern area’.

Moreover, Singapore also had considerable strategic importance because Britain’s Singapore Naval Base provided a centre for operations against Japan.

At that time, Singapore was the key to British imperial interwar defence planning for Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific.

If Singapore had fallen, it also meant the Allied forces in Southeast Asia had also fallen.

On the same day that the Japanese was attacking Pearl Harbour, they simultaneously bombed Royal Air Force bases to the north of Singapore on the Malay coast.

By doing this, the Japanese successfully eliminated British air forces available to protect or retaliate the troops on the ground.

The British retaliated by sending the battleship ‘Prince of Wales’ and the battle ‘Repulse’ at the head of fleet of ships.

This efforts turned out futile as they both were torpedoed and sank into the sea.

Hence even before the Japanese troops even set foot on Singapore, they already destroyed the British naval and aerial capabilities.

2.The Battle of Singapore

Somehow, the British was really expecting the Japanese forces to attack from the sea at the south of Singapore instead of from the Malay peninsula where treacherous jungle and mangrove swamp covered the region.

The British commander at the time, Arthur Percival had about 90,000 men at his disposal.

After the Japanese had attacked Kota Bharu just after midnight on Dec 8, 1941 right before the attack on Pearl Harbour, it marked the beginning of Japanese invasion of Malaya.

The Japanese assaulted their way from there heading south towards Singapore.

By Feb 8, 1942 with only around 23,000 troops, the Japanese forces which led by General Tomoyuki Yamashita entered Singapore.

Despite being outnumbered three to one, the Japanese managed to gain a strong foothold in Singapore.

One factor which contributed to that was Percival’s miscalculation in locating his troops.

Even though the British forces were far superior in number, they were were spread so thinly.

This allowed the Japanese forces to easily overwhelmed them by attacking the weakest part of the line.

Just seven days later, Percival decided to surrender to prevent further loss of life.

3.The Japanese called the Fall of Singapore ‘the bluff that worked’

On the evening of Feb 15, Percival tried to negotiate with Yamashita on the some of the conditions for the surrender of Singapore.

The British Lieutenant-General wished to delay the ceasefire so that all of his men to receive their orders on time.

In the same time, Percival wished to keep 1000 of his men armed in case that the Japanese would retaliate against the local populations.

Yamashita, however, threatened to carry on the planned attack for that night if the British did not surrender.

This was all a facade on Yamashita’s side. He was actually afraid that the British might discover the real situation of the Japanese in Singapore.

What Percival did not know was that the Japanese had a smaller number of troops compared to the British.

Furthermore, the Japanese were at the end of their supplies with literally only hours of shells left.

If Yamashita and Percival were to play a game of poker, now we know who would be the winner.

4.Winston Churchill called it the worst disaster in British Military History

When the Battle of Singapore first started, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered Percival to fight to the last man standing.

Hence imagine the shock Churchill received when he received the news that Singapore had fallen.

He called it the ‘worst disaster’ in British military history.

Later in his book The Hinge of Fate, Churchill blamed himself for the lack of fortification in order to prepare for the war.

“I do not write this in any way to excuse myself. I ought to have known. My advisers ought to have known and I ought to have been told and I ought to have asked. The reason I had not asked about this matter, amid the thousands of questions I put, was that the possibility of Singapore having no landward defences no more entered into my mind than that of a battleship being launched without a bottom.

“I am aware of the various reasons that have been given for this failure: the preoccupation of the troops in training and in building defence works in Northern Malaya; the shortage of civilian labour; pre-war financial limitations and centralised War Office control; the fact that the Army’s role was to protect the naval base, situated on the north shore of the island, and that it was therefore their duty to fight in front of that shore and not along it. I do not consider these reasons valid. Defences should have been built.”

The Fall of Singapore left the prime minister feeling in disgrace. According to his personal physician Lord Moran, it left a scar in his mind.

Moran wrote, “One evening, months later, when he was sitting in his bathroom enveloped in a towel, he stopped drying himself and gloomily surveyed the floor: ‘I cannot get over Singapore’, he said sadly.”

5.Was Arthur Percival to be blamed?

When things go south, it is natural for the blame game to start.

As for the Battle of Singapore, most fingers turned toward Percival.

His critics blamed him for not building the fixed defences in either Johor or the north of Singapore.

When his chief engineer Brigadier Ivan Simson requested to start construction in the area, Percival dismissed him with the comment, “Defences are bad for morale for both troops and civilians.”

Furthermore, teamwork was not in the Allied forces’ dictionary during the Battle of Singapore.

He was not in tune with Sir Lewis Health who was commanding Indian III Corps and Gordon Bennett who was commanding the Australian 8th Division.

Ultimately, Percival’s willingness to surrender to the invading Japanese forces was seen as undermining the British power in Southeast Asia.

Percival became a POW was sent to a camp near Hsian, China.

He was freed by an American intelligence agency, the OSS (Office of Strategic Services) as the war drew to an end.

After that, he went to the Philippines to witness the surrender of the Japanese army there.

In a twist of fate, Percival was ‘reunited’ with his old nemesis General Yamashita there.

Reportedly, Percival refused to shake Yamashita’s hand during their unexpected reunion as he was angered with the mistreatment of POWs in Singapore by the Japanese.

6.The escape of Australian general Gordon Bennett

Apart from Percival’s controversial decision to surrender, another person who came under scrutiny was Australian Lieutenant General Gordon Bennett.

On Feb 15, when Percival was negotiating about the surrender, Bennett decided to escape from Singapore.

After handing the command of the Australian 8th Division to Brigadier Cecil Callaghan, Bennett took a sampan with some junior officers and local Europeans crossing the Strait of Malacca to the east coast of Sumatra.

From there, the group proceeded to Padang on the west coast of Sumatra and then to Java before flying to Melbourne on Mar 2, 1942.

While Bennett was busy escaping, almost 15,000 Australian soldiers were captured in Singapore.

Unsurprisingly, Bennett’s choice to abandon his move was heavily criticised.

On Nov 17, 1945, the Prime Minister of Australia appointed Justice Ligertwood to be a commissioner to inquire into the action of Bennett relinquishing his command and leaving Singapore.

Later in his report, Ligertwood stated, “At the time General Bennett left Singapore he was not a prisoner of war in the sense of being a soldier who was under a duty to escape. He was in the position of a soldier whose commanding officer had agreed to surrender him and to submit him to directions which would make him a prisoner of war.

“Having regard to the terms of the capitulation I think that it was General Bennett’s duty to have remained in command of the AIF until the surrender was complete.

“Having regard to the terms of the capitulation I find that General Bennett was not justified in relinquishing his command and leaving Singapore.”

7.What you should know about Japanese Tomoyuki Yamashita

Thanks to his accomplishment conquering Malaya and Singapore in 70 days, Yamashita earned the nickname “The Tiger of Malaya”.

Most people do not know that the man behind “The Tiger of Malaya” was in a way, a believer of peace despite his proven successful achievements in leading his men in battle.

When he was promoted to lieutenant-general in November 1937, Yamashita insisted that Japan should end the conflict with China.

Moreover, he proposed to keep peaceful relations with the United States and Great Britain.

Clearly, Yamashita’s proposal was ignored.

Fast forward to WWII, he was the man who led Japan to victory in Singapore against Britain.

He was assigned to defend Philippines at the end of the war and was able to hold on to part of Luzon until Japan Empire formally surrendered in August 1945.

After the war, Yamashita was tried for war crimes committed by troops under his command during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.

The American military tribunal in Manila tried him for the Manila massacre and many atrocities against the civilians and POWs in the Philippines.

Even though Yamashita denied giving the orders for these war crimes and denied having any knowledge of these events, the court found him guilty. He was sentenced to death by hanging.

In his final statement right before he was hanged, Yamashita named and thanked the American officers who were in-charge of him during the military trial.

He also said that he did not blame his executioners and pray that the gods bless them. Yamashita was executed on Feb 23, 1946.

His controversial trial led to what the military all over the world now know as the Yamashita Standard.

It is when a soldier “unlawfully disregarding, and failing to discharge, his duty as a commander to control the acts of members of his command, by permitting them to commit war crimes.”

The overall situation was irony for Yamashita as the first orders he gave to his soldiers at the start of WWII was “no looting, no rape, no arson.”

8.The aftermath

Nonetheless, the Fall of Singapore resulted in the largest British surrender in history with a total of a nearly 85,000 personnel including Australians captured and about 5000 were killed or wounded.

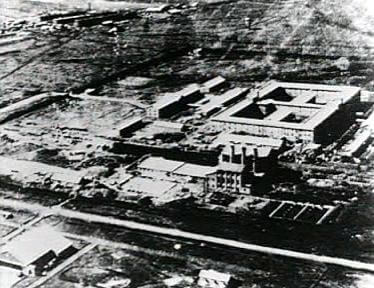

Thousands were held captives in Singapore’s Changi Prison and thousands others were sent to other parts of Asia.

Many of them who boarded the infamous hell ships did not survive the journey.

A huge number of the captured Allied forces found themselves working as forced labour on Burma-Siam Death Railway, Sumatra Railway and Sandakan Airfield.

Unfortunately, many POWs perished during their internment.

Throughout the entire 70-day campaign in both Malaya and Singapore, about 8,708 Allied forces were killed or wounded while the Japanese forces suffered from 9,824 casualties.

The Fall of Singapore also marked the beginning of Japanese occupation of Singapore.

Singapore was renamed Syonan-to meaning ‘Light of the South Island’.

During this time, the local Singaporeans suffered great hardships under the rule of Japanese.

The Chinese people in particular were targeted by the Japanese due to the Second Sino-Japanese War with thousands were murdered in the Sook Ching massacre.

Finally, the island was returned to British colonial rule on Sept 12, 1945 following the formal signing of Japanese surrender.