Do you know there is a Japanese building in Kuching?

When the Japanese forces first landed in Miri on Dec 16, 1941, they had successfully captured Kuching by Christmas day.

For over three years, the Japanese occupied Sarawak where the Imperial Forces introduced Japanisation, requiring the locals to learn Japanese language and customs.

Despite these efforts, only a few remnants of the Japanese occupation can still be seen to this day in Kuching.

One of them is Batu Lintang camp which was originally the British Indian Army barracks, while the other stands between India Street and Carpenter Street and was aptly named The Japanese Building.

The Japanese Building, an administrative centre for Japanese forces

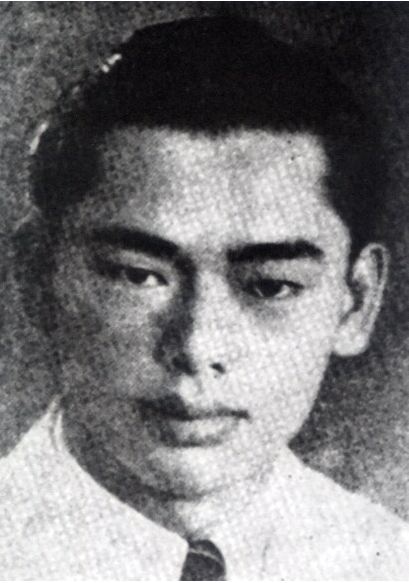

During World War II, Lieutenant General Marques Toshinari Maeda was elected the first commander of the Japanese forces for northern Borneo.

Initially, his headquarters were in Miri before he decided to move them to Kuching.

In Kuching, the Japanese used the Old Courthouse as their administrative centre. Then in 1941, they decided to build a building – The Japanese Building – to link the Old Courthouse and the Treasury Building.

The Treasury Building was built in 1929 purposefully for the offices of Treasury and Audit departments.

Before this building existed, there was a road connecting Carpenter Street and Indian Street passing between the Old Courthouse and the Treasury Building.

Before this building existed, there was a road connecting Carpenter Street and Indian Street passing between the Old Courthouse and the Treasury Building.

The blood and sweat of Prisoners of War (POWs)

The Japanese Building was built with the blood and sweat of POWS who were interned at Batu Lintang Camp.

They had to walk 3 miles in the morning from the camp to the site and walk back again in the evening.

Besides building this administrative centre, POWs together with male civilian internees were also forced to work at Kuching harbour, 7th Mile landing ground and other sub-camps.

Most POWs were Brookes’ officers, officers from North Borneo, Royal Netherlands East Indies Army officers, British Indian Army personnel and Netherlands East Indies soldiers.

Meanwhile, the civilian internees were Roman Catholic priests and missionaries as well as British civilians.

The Japanese paid those who were part of the work party with “camp dollars”. There were also called “banana money” because the picture of banana trees printed on the notes.

Life after World War II

After the Japanese surrendered unconditionally on Aug 15, 1945, the building was first used as the court’s library.

Over the years, it has served different purposes by various parties. Although the inside of the building is inaccessible to the public on a daily basis, it still opens its doors occasionally.

Located awkwardly between two of Brooke’s buildings, the Japanese Building is the only construction built by the Japanese Army that still exists in Kuching.