In 2014, former Social Development Minister Tan Sri William Mawan urged the Sarawak State Museum to research more on the history of the late Uyu Chandi.

Also known as Uyu Apai Ikum, he was one of the frontline warriors of Iban hero Rentap Libau.

According to Mawan, the late Uyu was considered a ‘Raja Berani’ by the Ibans.

Uyu and his fight against the White Rajah

Little is known about this Iban warrior except that as Mawan had stated, Uyu was one of the brave ones who had risen up against the Brooke government.

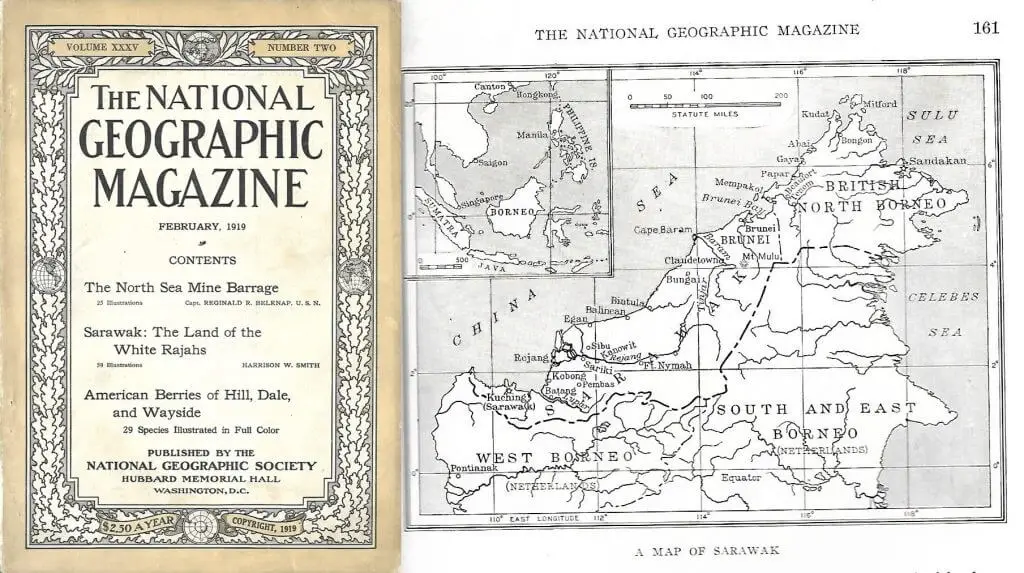

The war between the White Rajah and the Ibans of Saribas started in June 1843 and it continued on for the next two decades.

Finally in October 1861, Charles Brooke summoned two Iban leaders, Orang Kaya Pemancha (OKP) Nanang and his brother Luyoh to a meeting.

The Ibans were asked to pledge 400 tajau rusa (jars) as proof of their surrender.

If they did not cause any trouble within the next three years, these jars would be refunded to them upon the expiration of the agreement.

OKP Nanang and Luyoh as well as their followers agreed with the proposal. On their behalf, they sent one of their loyal old warriors, Uyu Apai Ikum to pay the fine.

After the fine was paid, OKP Nanang and his followers moved away, leaving Rentap to continue with the war.

Instead of surrendering, Rentap and his warriors retreated elsewhere until they finally settled down in Ulu Wak, Pakan. There, Rentap died of old age in 1870.

Uyu’s lumbong

More than a century after Uyu’s death, his grave or lumbong in Iban became a subject of study for a Japanese researcher. A lumbong is a grave site on stilts.

Motomitsu Uchibori gathered some oral history about Uyu for his paper ‘The Enshrinement of the Dead Among the Iban’.

After his surrender to Brooke, Uyu migrated to Julau and established a longhouse near a hill called Bukit Bulie. He later died of old age and was buried in a lumbong on the summit of Bukit Bulie.

Uchibori stated, “Uyu is said to have been a brave man, having taken five enemy heads and being capable of assuming the leadership of a small headhunting party (kayau anak).”

There were five others buried near Uyu due to their relationships with him. One of them was Uyu’s brother named Linggang.

Although he is said to have taken enemy heads, Linggang was not a leader like Uyu.

Hence, he was not ‘qualified’ enough to have his own lumbong. Meanwhile, the identities of the rest of the bodies remain unknown.

They were either brothers, sons or relatives of Uyu who wanted to follow this Iban warrior even after death.

As for Uyu’s lumbong, it is an important historical site that must be preserved for future generations.