There is a commonly known joke among Sarawakians that the level of English proficiency is correlated with the level of alcohol in your system.

So the more intoxicated you are, the better you can speak English.

In fact it is scientifically proven that alcohol helps you speak a foreign language better. This is because alcohol can lower your inhibitions, making you slowly overcome your nervousness and hesitation.

A sudden fluency in English language is not the only side effect of Sarawakians’ drinking culture.

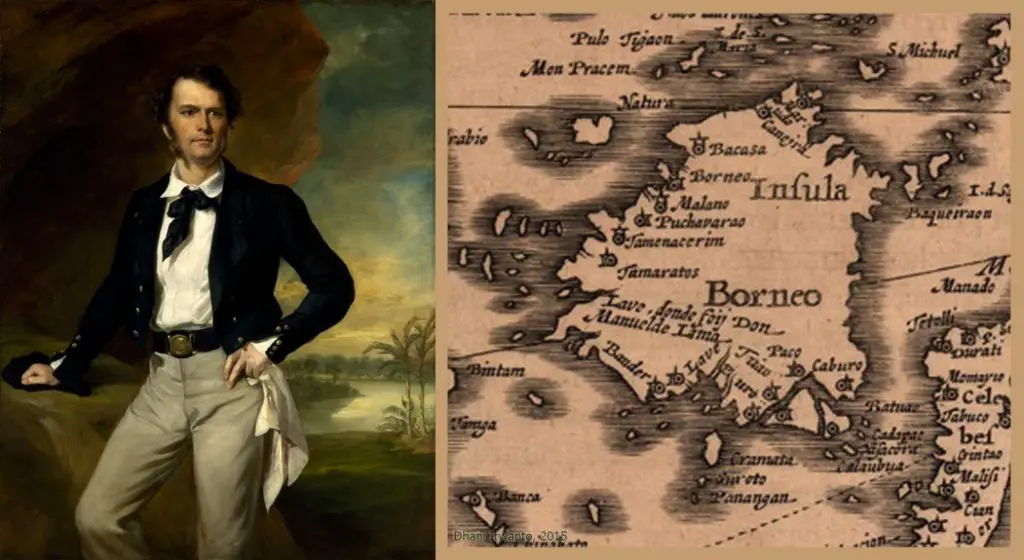

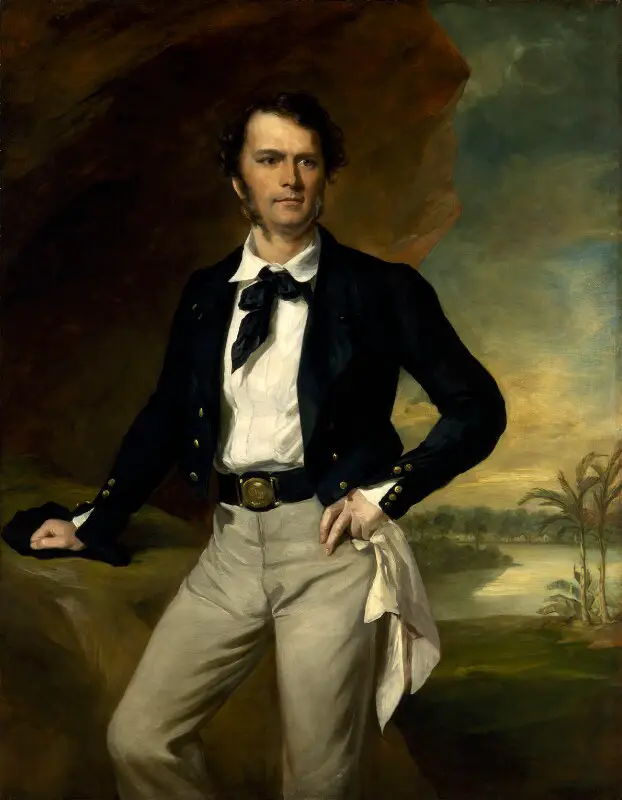

Back in the 1930s, Sarawak Museum curator Edward Banks visited different communities in Sarawak to observe alcohol consumption among them.

It is amusing to look back and see how much we have (or haven’t) changed over the past 80 years.

Here is Banks’ findings on Sarawakians’ alcohol consumption which was published on the Sarawak Gazette on Jan 4, 1937:

1.The Bidayuhs in Kuching and Serian

The Land Dayaks of the Kuching and Sadong districts in western Sarawak prepare a very sweet, yellowish-brown and clear drink from a medium-sized reddish-orange fruit known as tampoi, by which name they also call the beverage.

The analysis of tampoi from a Land Dayak house at Sennah, Sarawak River is as follows: alcohol (23%), sugar (5%) and acidity (8%).

The Land Dayaks are a timid somewhat forlorn people who have never really recovered from centuries of oppression, and though they will drink a little with a guest, or on special occasions, they have a quite unnecessary dread of doing something original whilst intoxicated, and so they only fall quietly asleep without making any trouble; indeed, they are not in any case a quarrelsome people.

2.The Ibans

The Sea Dayak or Iban brew is sweet and milky, and is known as tuak. It has much the same potency and after-effects as the others, reaching about 20% alcohol by volume.

The Sea Dayak upcountry is a singularly sober person on his own account, and it is probable that no alcohol passes his lips for months at a time; this is not because does not like it particularly, for he will take what he can in bazaars or from traders, although even this amounts to very little, for he is too shrewd and thrifty to spend his money in this way.

When drinks (usually European spirits) are free, both men and women will drink astonishing quantities “neat” without at the time showing any ill-effects, and the Sea Dayak’s usual sobriety is partly a matter of thrift and lack of opportunity.

On the few occasions during the year, usually in connection with the crops, when a feast or begawai is held, the Sea Dayak men and women may sometimes make up for their normal abstemiousness by drinking to excess, vomiting and then drinking again, this process making a begawai utterly undesirable to attend more than once.

On these occasions the Sea Dayak is somewhat more truculent and aggressive than usual, but fortunately he reaches a state of helplessness before serious quarrels can happen, and there are as a rule no permanent ill consequences.

Apart from this, Iban hospitality in the upcountry districts is showered on the visitors by a long line of girls, each bearing a bowl of drink, each dressed in her best and singing a short song of welcome before presenting the offering.

As nobody wishes to drink eight or ten glasses of doubtfully clean rice spirit, the later glasses may be shared with the givers or any willing helpers so long as a few sips are taken, and drink is not as a rule dished out to all and sundry, the object being rather to stun the visitor, leaving themselves in full possession of their wits.

3.The Kayans and Kenyahs

Drink plays a very large part in the life of Kayans and Kenyahs, no births, marriages and deaths are complete without a liberal supply for anyone who cares to attend, the long and self-imposed pantang periods in connection with their crops are relieved to some extent by the “cup that cheers,” and the stranger within the house may receive a “wet” welcome according to his inclination and the state of his hosts’ resources.

Nothing, probably, is freer than burak, as they call it, and even if one does not wish to drink deep, it is usually necessary to take a few sips in order to show that there is no ill feeling, and although the Kayans and Kenyahs are philosophical enough to accept an absolute teetotaler and not insist, they do not profess to understand it.

It is clear at once that the necessary large supply of yearly liquor cannot be brewed save from very abundant crops, and as these are vary greatly during hard times, sweet potatoes are sliced up and sugarcane crushed and either mixed with a certain amount of cooked rice, or allowed to ferment alone.

Individual Kayan and Kenyahs can consume without apparent effect quantities that beggar description of their own drink or of neat European spirits, and as a race they hold their liquor extremely well. Among themselves quarrels when in drink are rare, any anyone who inclines to become obstreperous or wants to be ill is removed at a sign from the chief or head of the house, and does not return; even those who have “drink taken” maintain a commendable equilibrium, and though possibly extremely cheery, keep well within the bounds of good behaviour.

The effect of social class system in Kayan and Kenyah communities

These people, are divided into social classes, and men of the ruling classes who see their followers going on the spree automatically restrain themselves a little, and though they join in and are by no means spoil-sports, they yet preserve a sufficient detachment instantly to intervene in any possible over-exuberance, and if they and their visitors want to “let go” they retire some other time to their own room and enjoy themselves as much as they like, their followers leaving them to it.

Already possessed with a considerable sense of humour, the influence of burak increases their sense of companionship, and mitigates rather than aggravates differences and quarrels, apparently nothing said or done on these occasions being afterwards used as evidence.

An European returning from two month’s tour was once “overtaken” in the first Kayan house to be reached, and subsequently discovered from some Malays, and of course teetotalers, that he had stayed there two nights, although he only remembered the first one.

On meeting these Kayans later he mentioned his lapse, and hoped all had been well while he was “out,” and his memory a blank; they replied that they pretty sure that nothing untoward had happened although they could not be quite certain, since they, too, had drink deep, and their memories were also blank.

A most gentlemanly gesture, and one which to this day has prevented the European concerned from finding out what exactly did happen.

4.The Kelabit

There are several kinds of Kelabits, and whilst a few probably make drink of nightly habit, there are other who do not make it a routine, though I do not suppose a week passes but that they have one or two cheerful nights.

Partly owing to the nature of the soil where they live, and partly through their very considerable industry their rice crops are larger and frequent, seldom failing, and by this means they are able to supply themselves with plenty of food and with about an equal sufficiency leftover from which to brew drink.

Their hospitality is amazing, and should upwards of a hundred people descend on a house, never very large, they are dined and wined freely as a point of honour, and there is no sign of stint. If they have notice of distinguished visitors they will brew burak as good as that made by most Kayans and Kenyahs, but in the ordinary way it is cooked rice and water, which never gets a chance to last long enough to be particularly appetizing to a European taste.

Though they can stand a vast amount of drink, they are eventually overcome, and though unduly cheery and quite polite, they then become rather stupid and a nuisance, usually being led quietly away by some one more sober-minded.

For all this, the Kelabit is not an out-and-out drunkard, a hard worker as these things go in Borneo, he will entertain visitors up to the limit, and if he hasn’t any visitors handy he will send out and invite his friends from the next house.

One therefore sees alcohol carried somewhat to an excess yet without offence among Kelabits, and though their state of inebriation as a rule surpasses though their state inebriation as a rule surpasses that of the others they are far from being habitual or daily drunkards, and there is no sign of their fertility or their considerable ability or energy being seriously impaired.

5.The Muruts of Limbang and Trusan rivers

… Murut has nearly drunk himself out of existence, and illustrates the evils of excess just as the Western people conform to the vicissitudes of abstention.

One may see a man come home from his farm and after food settle down to his own jar until he falls over sideways to sleep without going to bed, and wakes where he fell to stagger off to work next morning.

Many of them still live at heights of two, and three thousand feet like the Kelabits, but others are settle down country and the drink is a serious question with them all, for there is nothing like the conviviality of the Kelabits, Kayans and Kenyahs.

In parts, it has even become a competition; as elsewhere, a large jar full of drink is tapped at the mouth by two bamboo tubes, through one of which one must suck the beverage, while in the other is a float attached to a most aggravating little pith-gauge at the the top.

It is one’s painful duty by sucking the one tube to lower the gauge the necessary half-inch-or so prescribed by custom.

The competitive spirit arises to see who can sink the float the furthers, and there are ways and means of mixing it or making it stick to fool the boastful entirely foreign to the jovial convivial drinking parties of some of the other tribes.

Edward Banks’ conclusion of Sarawakians’ alcohol consumption

One therefore sees in the West of Sarawak Land Dayaks only who drink a little on special occasions, and are abstemious partly from lack of desire and partly fear of inebriation.

Further North are the Sea Dayaks, who, when left to themselves are abstemious from thrift or also from lack of desire, or for the sake of their health, but who let themselves go to the limit a few times a year on special occasions.

Then the Kayans and Kenyahs, to whom drink a necessary and frequent custom, but with whom it is not overdone to the extent of impairing fertility, health, strength or good behaviour.

The Kelabits, of whom it can only be said that they drink deeply and cheerfully when occasion arises, but that they are not so far impaired in health fertility, carry it a stage further, but their Murut cousins have overstepped the border, their drinking being neither jovial nor convivial but just a beastly debauch with consequent deleterious effects on their numbers and constitution.

What do you think? Do you agree with Banks’ observation on Sarawakians’ drinking habits? Let us know in the comment box.