The Battle of Lintang Batang was one of the many skirmishes which took place between the Skrang Iban led by the famous warrior Rentap and the Brooke government of Sarawak.

One of the historical significance of this battle was that a government officer named Alan Lee was killed and beheaded. His friend William Brereton, however, survived the battle.

Allegedly, Lee’s head was nicknamed “Pala Tuan Lee ti mati rugi” (Lee’s head who died lost).

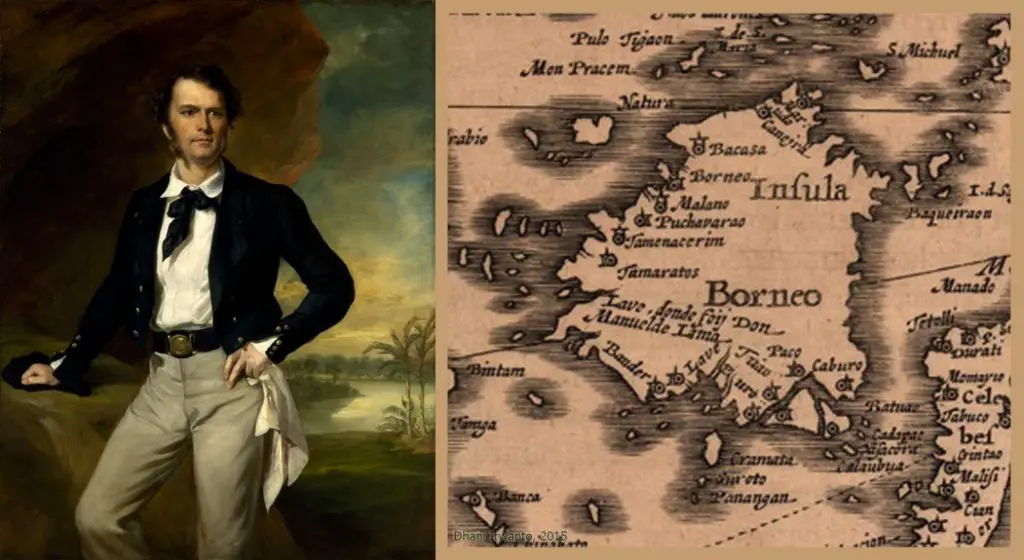

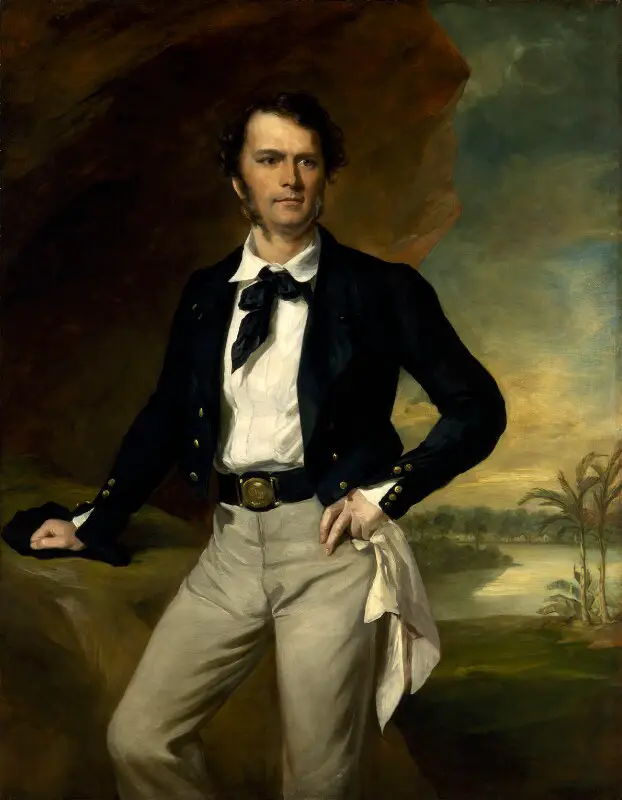

James Brooke recruiting Alan Lee and William Brereton

According to Cassandra Pybus in White Rajah: A Dynastic Intrigue, Lee and Brereton were recruited in 1848, making them some of the earliest European officers to work in Sarawak.

Pybus stated, “Returning from England in 1848, the Rajah brought much-needed reinforcements: Spenser St John, the son of an old friend, was to be the Rajah’s private secretary; Charles Grant was to be his personal secretary; and Brooke Johnson was to be aide-de-camp and hold the title Tuan Besar. Brooke Johnson, who had changed his name by deed poll to Brooke Brooke, arrived almost immediately after the Maeander, on another ship which also carried Henry Steele and Alan Lee, young recruits with an eye for adventure.

A further recruit was Willie (William) Brereton, whom the Rajah had affectionately taken under his wing as a 13-year-old midshipman on the HMS Samarang, stranded in Kuching for several months in 1843.

Now Willie was 18 and he too had given up the naval life for the Rajah of Sarawak. In Kuching all these young men made a jolly group around James Brooke, creating what Harry Keppel wryly called “The Rajah’s bower”.

Brereton was in-charge of Fort James at Skrang while Lee was heading Fort Lingga near the mouth of the Batang Lupar.

The Battle of Lintang Batang according to Steven Runciman

There are several accounts recorded on what happened during the Battle of Lintang Batang 1853.

In The White Rajah: A History of Runciman from 1841 to 1946, Steven Runciman pointed out the battle took place when Rajah was in Sambas.

Runciman wrote, “Early in the spring of 1853 Brooke (James) heard of a pirate fleet setting out to intercept it. It may be that he was deliberately misled; for the real trouble broke out elsewhere. The main agent in reviving Saribas piracy was a chieftain called Rentap. He had, even after the battle of Batang Maru, opposed the idea of any compromise with the Europeans; and he had proved his mettle and won great prestige by conducting a profitable raid against a Chinese village near Sambas and by defeating the praus sent by the Sultan of Sambas and the Dutch to pursue him.

“He particularly resented the Skrang Dyaks, whose most influential chief, Gasing, had made close friends Brereton and was now a loyal supporter of the Rajah.”

With the Tuan Besar away off the coast to the west, it was a good moment for Rentap to attack the Skrang. This news reached Brereton, who summoned Lee from Lingga to his aid.

They collected as many loyal Iban and Malay followers they could.

Lee wished to remain on the defensive in the fort at the mouth of the Skrang. However, Brereton insisted on moving to the stockade up the river.

When Rentap’s fleet appeared around the river, the government fleet immediately attacked them.

Brereton hastily joining the fight, found himself running straight into Rentap’s main fleet which was hidden behind the bend.

Lee followed to rescue Brereton and there was a sharp battle.

“Brereton just escaped with his life, but Lee was mortally wounded,” Runciman wrote. Rentap’s son-in-law Layang reportedly killed and beheaded Lee.

As for the battle, heavy fire from the stockade then forced Rentap’s warriors to retreat upriver. There, they came under attack from another Iban chief who was on Brooke’s side. In the end, 20 longhouses of Rentap’s supporters were burned.

Why did Lee decide to attack?

Meanwhile, J.B Archer, the last chief secretary to Rajah Vyner Brooke wrote briefly about what goes behind the battle in The Sarawak Gazette on June 1, 1948.

According to Archer, Brereton accused his friend Lee of cowardice for refusing to advance upriver and attack the enemy.

Lee, who was in command, suspected that Rentap and his men had prepared an ambush and did not want to walk into a trap.

“On the last evening the two had a violent quarrel and the next morning Lee, exasperated by his friend’s taunts, ordered an advance. Exactly as he had foretold happened. The Government forces were surrounded and outnumbered and Lee, up to his waist in water, met a valiant death defending himself with his sword against Dayaks all around him,” Archer wrote.

He added, “Brereton escaped but, they say, never forgave himself for his share in the disaster and died a year or two later.”

According to Archer, Lee was his ancestor. He pointed out, “I have tried many times to identify his smoked head which has been hanging in some Skrang Dayak longhouse as a trophy for nearly a hundred years.”

While Archer was not able to recover his ancestor’s head, he was able to recover Lee’s sword.

Both Lee (without his head) and Brereton were buried in the old Kuching cemetery overlooking Bishopsgate road.